Scene generation: "What do we want to see?"

Given the characters, genre, situation, relationships, and the concepts we have established: What do we want to see?

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

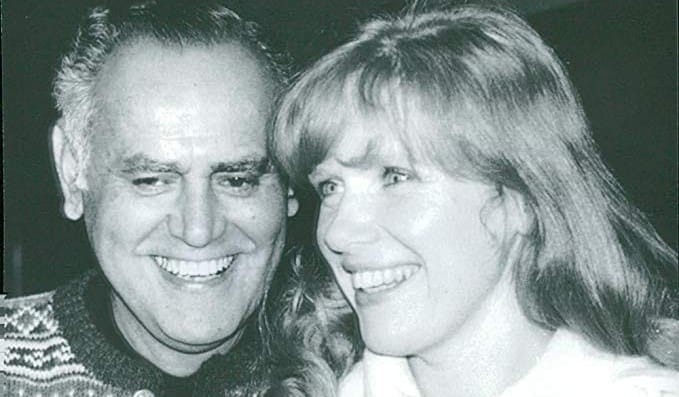

One of my early mentors, Joel Fields (THE AMERICANS and FOSSE/VERDON), taught me this trick. Joel got it from the late, great Steven Bochco, who gave us Hill Street Blue, L.A Law, and NYPD Blue.

It's pretty straightforward, yet I never consciously did it until Joel shared it with me, and now it's a trusted step.

The trick is to simply ask ourselves, "What do we want to see?"

This puts us in both storyteller and audience mode.

Given the characters, genre, situation, relationships, and the concepts we have established:

What do we want to see?

Remember, the ultimate goal is audience satisfaction.

That doesn't mean we are obligated to give the audience what they want, but we are obligated to provide them with an emotionally satisfying story.

Loose ends, premature endings, unanswered questions, abandoned set-ups and dashed hopes all undermine this satisfaction.

We seek a complete, thematically unified story that satisfies the audience. This means fully realizing our story's potential.

Why we too often skip past this.

When we first start writing, sometimes we're just happy to HAVE an ending! We're delighted to have enough activity to fill up the pages.

Sometimes, that mentality sticks with us. We write something, we end the screenplay, and we defend it. We argue WHY it should work rather than writing something that doesn't need such an argument.

I have also seen many take the angry young artist stance that they know better than the audience what should be in the screenplay.

Besides missing the point, you can guess how fun a read is from someone with an antagonistic relationship with the reader.

Others want the reader and the audience to be satisfied but never really look at their piece through the emotional journey the audience takes.

They're crossing their fingers, hoping it works rather than being the first person to take the journey themselves.

Sometimes, we don't realize what we introduce! We offer up a half-baked idea we thought was kind of interesting, only to drop it, but the audience is expecting it to get fully baked! And they're left hanging.

"What happened to that? I wanted to see her confront him on that!"

Most of all, we tend to worry too much about the plot.

We ask, "What can happen next?" rather than "What do we want to happen?"

Once we know what we want, we can think, "What needs to happen next?" And once we're in that mindset, we are seriously cooking.

Screenwriting is a lot to manage, and if the audience cares about it, you should care about it, too.

Asking "What do we want to see?" is one of the best ways to ensure that you maximize the potential of what you create.

How to ask the question.

If it's early enough in your project, this exercise should be done in the pre-outline phase.

It is part of scene generation.

If you're rewriting a screenplay, read the first act and then run this exercise to look at your screenplay differently.

Don't try to defend what you've already done. Fearlessly pursue this line of inquiry.

Then, read Act 2A and do it again.

Look at these areas:

- The premise.

- The world.

- The characters.

- The relationships.

- The concept.

What do we feel about them, and what are our expectations?

Given all these things, ask yourself, what do we want to see as all these things intersect?

Some examples:

WANTED (2008).

James McAvoy plays a timid man whose girlfriend thinks little of him and betrays him with his office best friend (played by Chris Pratt).

But McAcoy learns that he has the bloodline of a hyper-assassin and becomes a badass.

What do we want to see?

We want his ex-girlfriend to see him as a badass and Chris Pratt to get his comeuppance. So what does the story do? It concocts a way for McAvoy to go home and do just that.

FATAL ATTRACTION (1987)

In this classic thriller, Gwen Close originally killed herself and framed Michael Douglas. The test audience HATED it.

What do we want to see?

Again, we want comeuppance and we don't want our heroes without agency. The test audiences wanted Douglas' wife to get in on it! When they reshot the ending, that's exactly who shoots and kills Close's character.

CAPTAIN AMERICA: CIVIL WAR (2016)

A fight between The Avengers?

What do we want to see?

We want to see an all-out brawl! And that's what we get. One-half of the Avengers are fighting the other half of the Avengers. Most importantly, it comes down to an emotionally grueling battle between friends Steve Rogers and Tony Stark.

Next question: how do their special skills go up against all the other special skills?

The emotion of Civil War's third act is why it's my favorite Marvel movie.

Some common wants:

We want to see a protagonist use any previous or newly acquired skills.

We want to see a final beat for most relationships, good and bad.

We want to see secrets revealed.

We want awful people punished and their negative traits turned against them.

We want to see a confrontation between antagonistic forces.

We want to see new cinematic worlds fleshed out and fully realized.

We want to see questions answered.

We want to see any open loop closed.

My example

Most Wanted was the last screenplay I sold outright. We have a director, and we are out to cast now. I use it as a reference not because it's a perfect script but because I was there every step of the way, and it went through the process I teach.

This is the logline:

MOST WANTED - When a suburban family man suffering through a midlife crisis discovers his high school bully is on the police most wanted list, he drops everything in his life to hunt his bully down and capture him.

So look at these areas: "Mid-life crisis," "suburban family man," "high school bully," and "Drops everything in his life to hunt him down."

That's a lot! And this doesn't even deal with the relationships in the story.

Let's just take high school.

What do we think when we think about high school?

- I am in Texas, so I think about football.

- I also think about high school plays because that's what I did

- Cheerleaders.

- Cafeterias.

- Lockers.

- Bathrooms.

- Prom.

- Crushes and heartbreak.

- The teachers are friendly and not so friendly.

There is a version of this story where the high school is only mentioned, but who wants to see that? This guy has serious demons; we want to see him confront them!

So, in the original draft, I created a chase scene that ended up driving through a high school football game to get him back to his high school.

It was a fun set piece, and the chase eventually led into the school itself.

I also forced him to confront his high school crush, who wasn't very nice to him back in school, as well as the bathroom he was most tortured in.

This was just a portion of what I generated from asking, "What do we want to see?"

THE REWRITE

The third act was rewritten entirely in development. We took out the high school set-piece.

I argued that we needed to get our protagonists back to his high school, one way or another.

The character needs it, and the audience wants to see it.

There were ideas for a class reunion at the school, and I even wrote the scene, but it didn't work.

Finally, we used the trick where he had to retrieve something only available at the high school.

The football game was changed to a high school musical with kids and parents in the main hall. The high school security is curious why a grown man is lurking around the school with no kids that go there.

It's one of the more fun sequences in the script, and all comes from maximizing the premise by asking, "What do we want to see?"

Inspiration, not dictation.

"What do we want to see?" is meant to inspire and inform your scene generation, not dictate it. Do not feel beholden to your answers.

There is a term "fan service" for when storytellers try too hard to please a vocal part of their fan base. It's used when this concept becomes too cynical and undermines the story.

Your obligation is to surprise and delight and tell an emotionally satisfying story. That's all.

It remains your story to tell and no one else's.

That is until you sell it.

Want to go deeper?

If you want to learn more about generating great scenes for your story, check out my course Idea To Outline.

The course teaches you a time-tested, step-by-step professional process for turning any idea -- no matter how vague -- into a detailed scene-by-scene outline.

It also has a money-back guarantee. Either love it or get a full refund.

When was the last screenwriting class you took that was guaranteed?

Click here to learn more about Idea To Outline.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline