"What's the worst thing that could happen?"

Is it enough to transform the protagonist or the characters around them? If not, it may not be bad enough.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

Last week, I talked about making choices in your screenwriting.

This is the essence of my work as a screenwriting teacher: teach writers to make choices.

Infinite choices, after all, can freeze us up, and too often we let them.

But there are two primary pathways to make this task easier.

- Make BIG decisions up front that guide all the subsequent choices.

- Know what questions to ask to help make those choices.

This week, I want to talk about one of my favorite questions to ask. It's one of my favorites because it can be so much fun.

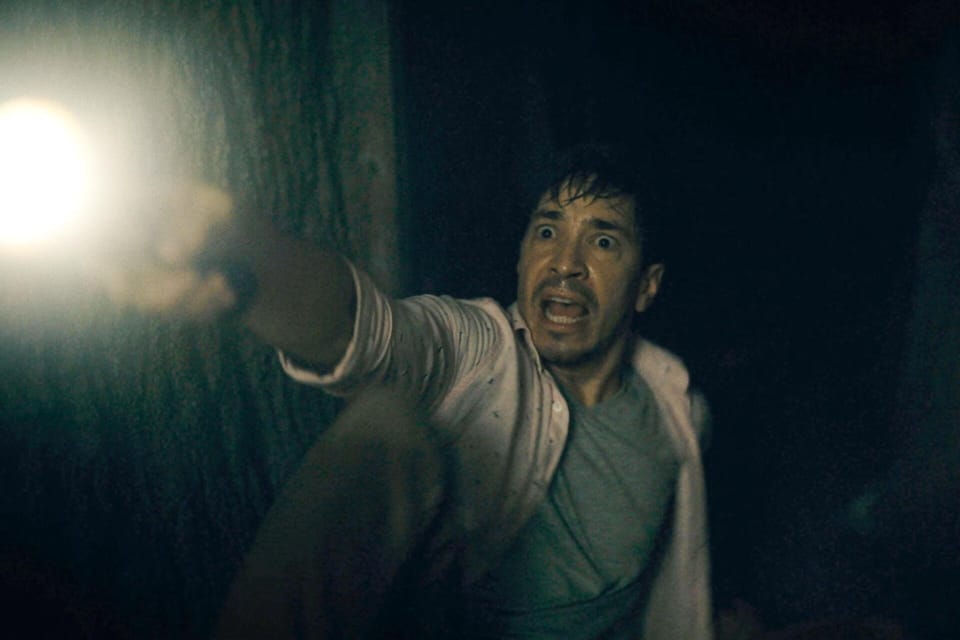

"What's the worst thing that could happen to your protagonist that they could still bounce back from?"

We need to add the second part, "that they could bounce back from," because the literal worst outcome would end the story right then and there!

So, we add that caveat to be completely clear.

Because what we're looking for from this question is something we're going to force the protagonist to actually endure.

We're going to force them through it. We're going to make them face it and decide how they will respond.

And if we do it right, that choice will mean something to them and to us.

(We're also talking within the story itself. Some stories are about what happens after the worst thing imaginable has happened!)

This is a universal moment across most story theories.

Blake Snyder calls it the "All is Lost" moment, McKee calls it the "Crisis," and Vogler, "The Ordeal."

I have also heard it called the "Death Experience" and "The visit to death."

I have a more pedestrian term: "The low point."

(I use the term "crisis" for the break into Act 3, and I regret it! I defined it early in my teaching, and it has not held up as I have become more specific about that moment. People often confuse it with the low point. I don't think it will last too much longer in my glossary.)

From a structural standpoint, I have found the low point more fluid in its position than most.

Old Hollywood structure often described the low point as occurring at the end of Act 2, but I think this is a misreading of "near the end of Act 2," which seems much more accurate.

For simplicity's sake, the easiest place to envision the low point is at the end of Sequence 5 (Sequence 5 is often longer than the other sequences)

These days, however, a prescriptive destination doesn't seem to fit as well for me anymore.

I'm now more interested in how the low point, the realization, the dramatic direction of Sequence 6, and the Act 2 break work together to dictate its placement.

That said, there will be a low point in your story, and it will serve a clear purpose.

Story is about change.

It is about transformation, and people don't usually change willingly. It takes hitting their own version of bottom.

The more a character transforms, the more drastic the low point usually needs to be.

Indiana Jones needs far less of a low point than Ebenezer Scrooge, while most characters will lie somewhere in between.

For characters who remain steadfast, the low point is a crisis of confidence.

This moment, this event, this terrible thing must test their core belief.

Do they really, truly believe this thing? Or is it something they're willing to give up when things get rough?

Their steadfastness, against all odds, inspires transformation in others.

Know your story. Know your character.

Know your dramatic question. Know what you're asking the low point to do here. What is your intention with it?

Is the low point simply plot-driven?

That is, the point where the dramatic question looks the least likely to be answered to our satisfaction?

This can work. But it's challenging! In RAIDERS, for example, the Nazis take both the Ark and Marion. Pretty simple.

Now, is anyone going to complain about RAIDERS?

No, it's perfect.

But getting the audience to really feel "Oh, no!" and be excited for one more push is harder than it looks. Pretty much everything there needs to be running on all cylinders (which, in RAIDERS, it is).

A more emotionally intense, horrible event is often easier.

And in the case of strong character transformations, necessary.

You can lean into that emotion to help the audience commit to the resolution.

Do we care about Barbieland becoming a patriarchy like we care that the Nazis just took the Ark and Marion?

Nope! But Barbie does!

And because we care about her, we care about Barbieland and, more importantly, Barbie's emotional well-being.

As always, don't settle.

Outside of simply not having one at all, a generic low point that doesn't evoke emotion is the biggest mistake screenwriters make.

They know they need to do it, so they phone something in.

But there are few things more boring than the feeling that a writer is painting their screenplay by the numbers.

Do not view the low point as a hassle or something you have to do.

The low point is an opportunity.

It's an opportunity to challenge your character. It's an opportunity to surprise and delight the audience and make them feel something.

That is, after all, why they're there.

You don't have to go with your first choice. Explore. Have fun.

This is why the question, "What's the worst thing that can happen?" is so valuable.

Dig deep here. Be imaginative. Avoid the obvious unless the obvious really, truly is the best course. Brainstorm. Have options.

Remember, all roads lead to this point.

What does the character fear?

Force them to face it. Are they afraid they aren't good enough? Are they afraid they're a failure? Tell them exactly that here. Make them work through it.

What has the character relied on?

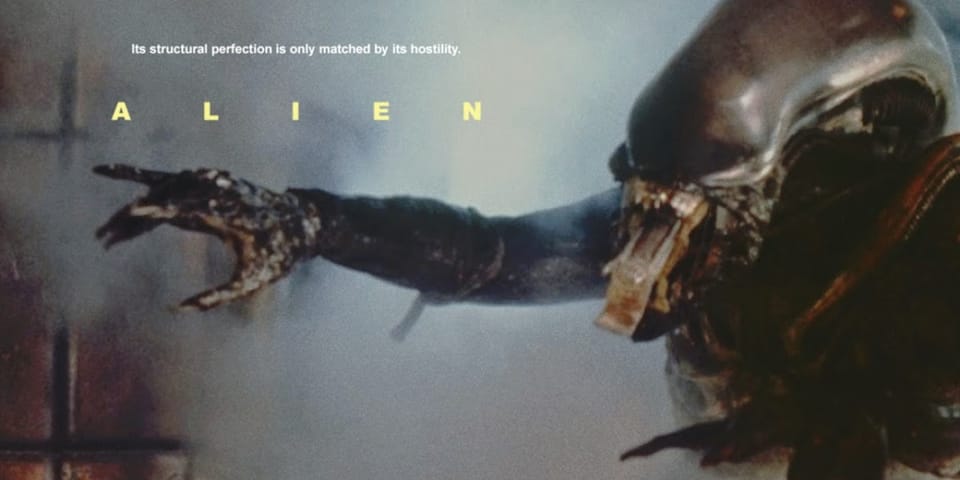

Take it away. Kill the mentor. This is the classic hero's journey. STAR WARS. THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING. In THE MATRIX, Morpheus is taken.

Remove the best friend, the believer. In TOP GUN, Maverick screws up, and Goose dies!

In EDGE OF TOMORROW, the only advantage the character has -- his infinite respawning -- is taken away. In the final act, if he dies, he dies.

Who do they think they are?

Tell them otherwise. One of the most stunning moments for me in all my years of moviegoing was in TOTAL RECALL, when he watches a video and discovers he's actually the bad guy.

I have tried to recreate this emotional experience countless times in my writing, and even tried again in the latest script, BACK UP!

Remove all their options.

In THE MARTIAN, his food supply is destroyed. Time is now limited. He must dig deep and develop a new plan immediately.

In GROUNDHOG DAY, not even his own death can save him. He must accept that he will continue like this forever. It's the exact opposite of EDGE OF TOMORROW because the dramatic question is different.

Sometimes it's just the weight of it all.

In BRIDESMAIDS, there are five failures in a row, which leads to a prolonged, lingering "Woe is me" sequence.

Some characters need time to absorb the hits and figure out who they want to be and what they want to do, but be careful not to drag the story to a screeching halt.

It works beautifully, and it's a great example of "stacking" low points to a culmination.

My last four screenplays.

Here are their low points.

MOST WANTED.

The dramatic question: Will he capture his high school bully?

I stack this low point. Sequence 5 ends when he chooses to help the bully escape. He wants to be the one to capture him, even if it risks his never being caught at all.

This leads to 1) His mentor abandoning him, 2) His wife having enough, 3) Discovering his son is a bully at school, and ultimately → He's told his family is now a target and in danger!

THE GOOD TEACHER

The dramatic question: Will she save her child from the nefarious teacher?

The low point is when Child Protective Services comes and takes her child away. She can no longer protect her child, and she's not sure who will.

ANOTHER LIFE

The dramatic question: Will she get away with this scam?

The low point is when the psychotic crime boss shows up, and she discovers she is now responsible for her fake husband's debt! She needs to pay up or they'll kill her.

BACK UP

The dramatic question: Will he solve the crime and find the killer?

It's an amnesia story. The protagonist is determined to find the killer and discovers that he was the bad guy all along.

Make it a scene. Make it emotional.

Of the examples above, including my own, only in BRIDESMAIDS and MOST WANTED is the low point simply shared information. But in both cases, the events are stacked with great scenes that lead to a culmination.

In all the other examples, the low point is a grueling, exciting, emotional scene itself.

We gasp in THE MARTIAN when all the food is wiped away. We are horrified in TOTAL RECALL, right along with the protagonist, when we find out he's actually the bad guy.

The first time we saw Obi-Wan Kenobi close his eyes and take Vader's lightsaber, our reaction was similar to Luke's.

- Great characters.

- Great scenes.

- The order in which we put them.

It's never too late to ask.

Even if you have written the screenplay already, look back and ask, "What is the worst thing that happens to the protagonist?"

Is it emotional? Is it an event? A scene? Is it enough to shake and challenge their view of themselves or the world around them?

Is it bad enough that their resilience through it would inspire and transform others?

Does it take us further away from the resolution we hope for? Perhaps so that it even seems impossible?

Does it demand a reaction that pushes us to the climax?

If it's not, it may not be bad enough.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

Tom Vaughan

Tom VaughanWhen you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline