What story are you telling?

There is so much going on in a screenplay, that we often forget the most important thing: You are telling a story.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

I worked with a screenwriter last week who is writing a biopic. It's a paid assignment with a director attached, and using the life rights of a living person.

The screenplay is based on the recounted tales of this individual, so there is a LOT of information to work with.

He's a talented writer, and the script is FULL of good, interesting scenes.

This is going to be a good movie. But it's not there yet.

Why not?

Mainly because it recounts a lifetime of repetitive details. There isn't a sense of movement beyond them. The plot itself maintains one steady direction until the inevitable conclusion we knew was coming.

If you were to take any 10 pages from the screenplay, you would be fascinated by those 10 pages. Seriously, it's good stuff and it's well-written.

Yet, when you combine all the pages, the whole is less than the sum of its parts.

So what happened?

It doesn't tell a story.

It thinks it does, because things are happening, but it's all plot.

Story and plot are not the same thing.

This lightbulb moment was so important to me that I named all my teaching after it.

But there is so much going on in a screenplay, as well as our own relationship to our creation, that we often forget the most important thing:

You are telling a story.

I define story for myself and for my students as:

The transformational journey of a human being.

It may be the protagonist who changes, or the people around them, but someone is changing.

This is the fundamental premise of my teaching, you've likely heard me say this before.

And I can guarantee you it will not be the last.

But it always bears repeating because we so often forget.

If we define our story simply and clearly, we give ourselves a unifying framework to help us narrow down the infinite options of our imagination to a single, strong choice that makes it onto the page.

Plot serves story.

If a screenplay is all plot and no story, it is a lot of sound and fury signifying nothing.

At best, forgettable.

At its worst, boring.

Remember, we don't really care about the plot. We think we do, only because it's the language we use to describe things.

But what we really care about is the emotional reaction to the plot. The character's emotional reaction and our own.

That emotional reaction adds increasing value to the emotional experience of the story, allowing the whole movie to be greater than the sum of its scenes.

Storytelling is an emotional exercise, not an intellectual one.

We are looking for an emotional ride, or an emotional catharsis, and the best stories give us both.

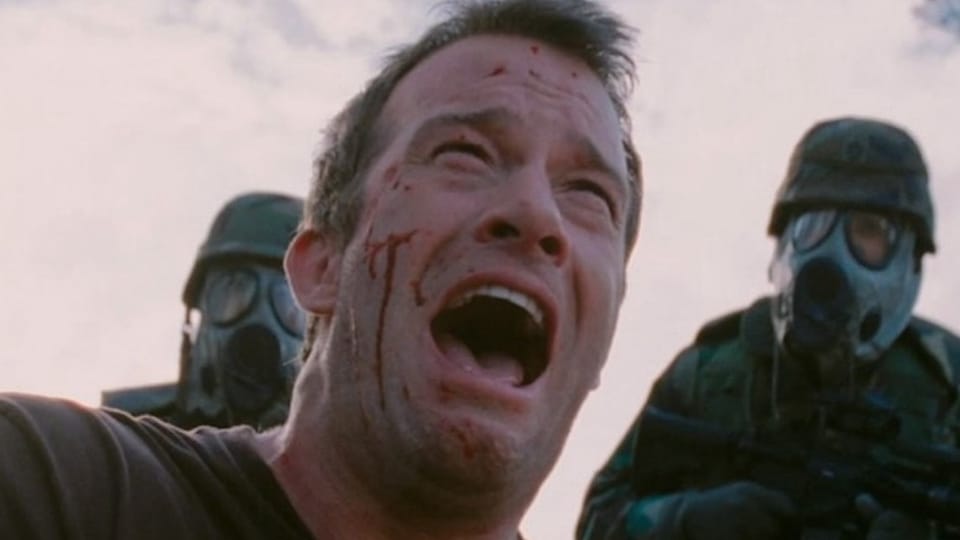

Even in the most plot-focused summer blockbuster like JURASSIC PARK: REBIRTH, we still see an attempt to find a sense of growth in the characters.

Of course, we are there for the dinosaurs, not character transformation.

We paid for a monster movie, damn it!

We want thrills, chills, close calls, and tension. We want to see certain people swallowed and certain people live.

Yet, we still want a sense of closure.

We still need that feeling that these events mean something beyond just the plot and the antics of a creature feature, even if it is perfunctory.

The audience needs and wants a unified tale that adds up to something more.

If we get the sense that's what we're getting, we stay more focused. Our attention is tighter.

And when we doubt it, we doubt the storyteller, and now the tale in front of us is competing with all those other thoughts in our head.

Suddenly, the grocery list we're procrastinating about is awfully compelling. Or maybe we need a snack.

Perhaps the math of how much sleep we're going to get is suddenly quite urgent.

Know what story you are telling.

A few weeks back we examined this question from the perspective of each individual scene, but here, I was to look at the macro.

What is the ultimate aim of all those scenes combined? They should build up to something more.

That "more" is the final emotional reaction to your story.

How do we decide that, and how do we keep from losing track of it?

Define your story.

"This is a story of (a person like this) who (goes through this) and becomes (this.)"

- or -

"This is a story of (this person who remains steadfast in this belief) and transforms those around them."

Know who the characters are at the beginning, and who they are at the end.

Decide how this transformation affects the relationships in the story.

Just like a character transforms, so should the relationships. The relationships will go the way of the story.

Define these transformations as well. What do the relationships look like at the beginning, and what do they look like at the end?

Know what emotion you want the audience to feel at the end.

When I say, "Know how it ends," this is what I mean, more so than the plot.

Do you want the audience to feel triumph? Vindication? Do you want them to feel hopeful or exhilarated?

A simple but overwhelming sense of joy?

Or is it anger or outrage? A sense of loss of what could have been?

While you should probably have a general idea of what brings this emotion about, like, "His relationships with his daughters are healed," or "He escapes and starts a new life," the specifics are not as important as knowing the emotion you want.

Story is the goal. Plot is the strategy.

The strategy only helps you if you know the goal.

This emotion is your end game. And everything that comes before it consists of the building blocks that get you there.

Map out the character's path there.

Know where your character is in their emotional journey.

Most stories will have five emotional throughlines defined by a clear want for each step, and that is usually about as complicated as I get.

The most I have ever seen is GROUNDHOG DAY, which has 8 distinct emotional phases, one for each sequence!

This step in the character's transformation is typically defined by a specific act or sequence.

At its most basic, think of a character's journey as:

- Act 1: Their old self in their ordinary world.

- Act 2A: Their old self, in a new world, trying to solve their problem. They fail.

- Act 2B (Sequence 5): The new world decimates their old self.

- Act 2B (Sequence 6): A new version of the protagonist is born.

- Act 3: This new version discards their old self and solves their problem.

The general structure is not the hard part. It really is as simple as it looks.

It's all the little steps in the structure that are challenging.

You need great scenes that bring about this transformation, and you need them in an order that builds upon each other.

And change is rarely gradual.

You need distinct scenes at the end of each throughline that lead to a new direction.

But as always, you can't really do any of this if you don't know where you're going.

Don't get bogged down in the details.

There is a great moment in Bull Durham where the confounded manager (played by the late, great Trey Wilson - a fellow Coog) hilariously tries to explain to the players that baseball is a simple game.

"You throw the ball. You hit the ball. You catch the ball."

Now, anyone who has ever tried to hit a major league breaking ball will tell you just how difficult "hit the ball" really is, but the goal itself is simple.

Someone tries to throw a ball past you, and you try to hit it.

It is the same with screenwriting.

The details are complicated, the skill required is more than we first realize, yet the simple goal remains the same.

Tell the story.

Someone wants something, they are having trouble getting it, and something will happen if they fail.

In the end, the resistance they overcome changes them or solidifies a core belief that changes the people around them.

We watch this journey for the emotion it evokes. And when we do it right, and we hit the sweet spot of the bat, we knock it out of the park.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline