What fear are you exploiting?

Fear works best when it is primal and taps into something much more profound than jump scares

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

I am working with a development client on a horror project. She has a great concept, but the outline focuses too much on plot and doesn't leave room for enough great scenes.

This rarely moves the needle for any project, but it's especially harmful for a horror film with a great concept.

The solution seems pretty straightforward, right?

More great scenes.

But how do we do that?

In this case, we do this by leaning more into the concept. If the concept is perfectly clear, this can be easy.

But sometimes we haven't defined the concept for ourselves, let alone why it's fun or compelling to begin with.

And if we don't know that, then we don't know the emotion we want to evoke with it.

Horror can make this easier because there is a question with horror that we can and should ask: "What fear does this story tap into?"

The fear is the concept.

I have written many times about the importance of concept as an external promise of what the movie is.

But it also provides a unified vision for us as storytellers. We are, after all, the ones who have to deliver on this promise.

In horror, the promise is tension and fear.

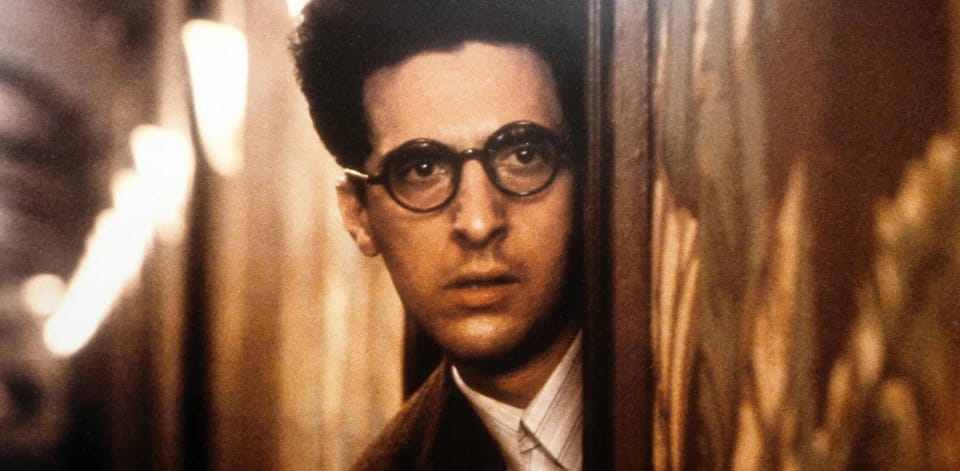

Fear works best when it is primal and taps into something much more profound than jump scares. This is why some horror stories stay with us, while other less engaging stories feel like cheap Halloween haunted houses.

Forgotten as soon as you walk out.

If your concept can exploit a universal fear — or perhaps even create one — not only does it give you guidance and focus on what will appear on the screen, but it assures you a much more intense emotional response.

It's not about the plot.

This is a common mistake with just about any kind of story, but it's a particular drag on horror (and comedy, for that matter).

Plot mechanics in horror can easily weigh down our story with details we don't need and explanations we don't want.

Once we start writing from a plot-first perspective, we almost certainly give up opportunities for more great scenes. Narrative drive is far more critical than a complicated plot that requires characters to explain it to each other and the audience.

The audience's energy is a limited resource, too.

Don't waste it on plot that adds no emotional value.

Too much thinking often leads us to think, "We'll make it scary when we get there."

My last two horror films were heavily rewritten. Tension was removed, and, for reasons that were never clear to me, more plot was added.

In both cases, directors insisted they could summon up the scares later when necessary as if horror were the easy part of a horror film.

It is not, and they never did.

They desperately turned to jump scares — some effective, most not — and both films were disappointing as stories and scary movies.

The fear in a horror film should never be a secondary concern.

It needs to be built into the story's DNA from the beginning.

Asking what can happen next is never as good as knowing what you (the storyteller) want to happen next.

And what needs to happen next to make this plot make sense is a very different question from what needs to happen to push this character where they're going.

What fear does the concept generate?

These are the horror concepts that make your job so much easier.

Identify what fear this story exploits.

The Exorcist exploits the helpless feeling of your child ravaged by forces beyond your control. (Many have claimed The Exorcist is about puberty, and while now, being a parent to a 12-year-old has made me more partial to this interpretation, I still don't quite accept it.)

Yes, there are questions of faith, guilt, and sacrifice, but a fear of the devil could take many forms. A fear of your child possessed by the devil is something else altogether.

Some others:

- Friday The 13th: Isolated out in the woods away from authority.

- Jaws: Fear of the water.

- Alien: Out in space with an unknown species and away from authority.

- Deliverance, Southern Comfort and Wrong Turn: Out in the middle of nowhere away from authority where the hillbillies are in charge.

- Invasion of the Body Snatchers: Everyone is changing and conspiring against you including authority.

- Halloween and When A Stranger Calls: Alone and babysitting.

Use this fear to generate great scenes.

Do not rely on your plot to do this. Do not convince yourself you will make it scary later. This is difficult to do once you have filled the screenplay up with plot.

Generate the scary scenes first.

Then figure out how the plot will connect them.

The Good Teacher.

This was the last horror screenplay I wrote. We did not sell it when I first wrote it, but we are now pushing ahead with a director and producer attached.

The development of it took even longer. It took ten years to move off my "possible ideas" list to my "active" list. This is because I didn't have a concept or a story.

I just had an idea for a film around a daycare center.

That was it. Which isn't much.

But one day, I dropped my new six-year-old stepdaughter off at school, and it occurred to me, "Who are these people watching her?"

We drop our children off at school and pick them up eight hours later, with no real idea of what happens to them in between.

And I found myself a fear to exploit.

What happens to our children when we are not around?

So, I started generating scenes built around that fear. I also gave the story a character convinced that everyone else knew how to parent better than her.

This gave me another fear.

The fear that we are a terrible parent and those in so-called authority know more than we do.

In the story, the teacher uses both of these fears against her.

Scenes that emerged:

- The teacher separates the child from the other kids at school and initiates an emotionally inappropriate relationship.

- The teacher introduces the child to her own cultish religion.

- In one harrowing scene with the child participating in an animal sacrifice, cutting back to the mother at work, completely oblivious and worried about party invitations.

- When the mother notices the change in the child's behavior, she makes inquiries at school only to be gaslit that something must be happening at home.

- The teacher files a complaint with CPS, leading to the child being removed from the home.

This may sound more like a domestic drama, but I haven't gotten into the demons yet, the black magic, and half a dozen dead bodies.

Nearly every signature scene was generated before I started outlining.

Sure, there were discoveries, and some ideas were replaced by better ones along the way, but the set-pieces were mostlygenerated in pre-outline, not the outline.

The outline phase was when I figured out where those scenes needed to go to best tell this story.

It's not just horror.

Though less vital, you can tap into fear for thrillers, dramas, and even comedy when the concept suits it.

- Cast Away: Alone and cut off from all of civilization.

- Shawshank Redemption: Wrongfully imprisoned.

- Gravity: Stranded with no way home and time running out.

- Unfaithful: Infidelity.

- In The Bedroom: The violent murder of a child.

- Beautiful Boy: Losing a child to addiction.

Interestingly, I found fewer recent non-horror titles that were good examples of this than I expected!

It's about great scenes and sequences.

Always.

Plot is just an excuse to generate emotion through characters and great scenes.

You will indeed discover great moments along the way but don't rely on that as a strategy.

Know your story, know your concept.

If you can't generate at least five great scenes with those alone, that project is likely not ready to move forward.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline