The vital job of Act 1 that not enough people talk about

A huge part of Act 1's job is to get the audience to believe the protagonists's often outlandish choice that drives us into Act 2.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

First acts are busy. There are character introductions, relationships to establish, worlds to build, and the inciting incident.

It's a lot.

At the end of the first act, the protagonist makes a choice, and then the narrative truly begins.

Whether it's Perseus, Luke Skywalker, Thomas Anderson (Neo), Elle Woods, Frodo, Diana Prince, or Barbie, the more out-of-character that choice is, the more exciting the adventure will often seem.

And there lies the challenge.

When it comes to emotional truth, we do not benefit from the audience's suspension of disbelief.

They either believe it or they don't.

Aliens, sure. Dinosaurs. Yep. Ghost? No problem.

Does anyone react to these things in an untruthful way? We call BS.

That is why a huge part of Act 1's job is to get the audience to believe the protagonists's often outlandish choice.

It is such a requirement we don't always appreciate the level of difficulty. But when done well, we won't even realize just how crazy the choice is.

We have to get to the story.

The more time we have to show a character make an uncharacteristic choice, the easier it is.

Michael Corleone has 74 minutes before he tells Sonny, "I'll kill them both."

That's comparatively easy to get him to do at the end of Act 1, just 25-32 pages in. I willn today's environment, we're going to want to lean closer to that 25 number.

As always, know what story you're telling.

The most common mistake I see is spending way too much time in Act 1 trying to get everything done so the protagonist's choice makes total sense.

It's understandable. We ask a lot from Act 1.

But it's not helpful. We just don't have that time. Both the story and what makes it special are on the other side of the Act 1 break.

You need to get there.

BARBIE is not a story about BARBIE in Barbie Land; it's about what happens when she leaves it.

A story about Demi Moore's character in THE SUBSTANCE finally breaking enough to do something desperate may be an interesting story on its own. But it's not THE SUBSTANCE.

The SUBSTANCE is about what happens after she does.

Which means we have to get there quickly.

The challenge is that you can't rush it.

This is the next biggest mistake. Rushing through Act 1 with only regard to information and plot, rather than moving a character from one emotional spot to another.

The screenplay either moves too fast, crams too much in, or both. This is a good time to remember that every act and every sequence has a job.

If a scene is not participating in that job by either making it happen truthfully or making it more compelling, it has to be considered expendable.

Character and events are your instruments.

Some characters make it easy. It's not difficult to get an action hero into the fight. What else is James Bond going to do?

Characters that want to be action heroes usually just need the right events to happen. Luke Skywalker wants to get into the fight; he only needs a push.

Frodo is another story. Frodo needs convincing from both events and the people around him.

Elle Woods from LEGALLY BLONDE needs to make the decision to follow her fiance to Harvard Law School.

This is not something she ever considered. It's completely out of character. The storytellers need to put her in such an emotional place that the decision makes complete sense.

But the much bigger challenge in that story is convincing us that she gets in!

And she needs to do so quickly because this is not a story of HOW she gets in but what happens once she does.

Granted, we are asked to suspend our disbelief a little here, but not on the emotional life of the protagonist.

The solution is hilarious, convincing enough that we agree to accept it, and leans into the entire concept of the movie.

Everything about BARBIE is perfect. She has no desire for anything to change.

That's the whole point of who she is in Act 1. But the story requires her in the real world. Something needs to motivate her to venture out on the hero's journey.

So they use that character against her and take away her perfection.

Going out into the special world is the only way to get it back.

Think of some of your favorite films.

A movie is about getting a character(s) from who they are at the beginning to who they are at the end.

Act 1 is about getting the character from who they are at the beginning to who they are, that makes the choice that breaks us into Act 2.

How does THE MATRIX get Thomas Anderson to swallow a little red pill from a large, intimidating man in leather, spouting cryptic conspiracy theories?

How does RATATOUILLE get Remy to agree to go back to the kitchen that caught him and ordered him murdered?

How does WONDER WOMAN get Diana to agree to leave her island for the first time in her life with a total stranger that has brought nothing but death to her people?

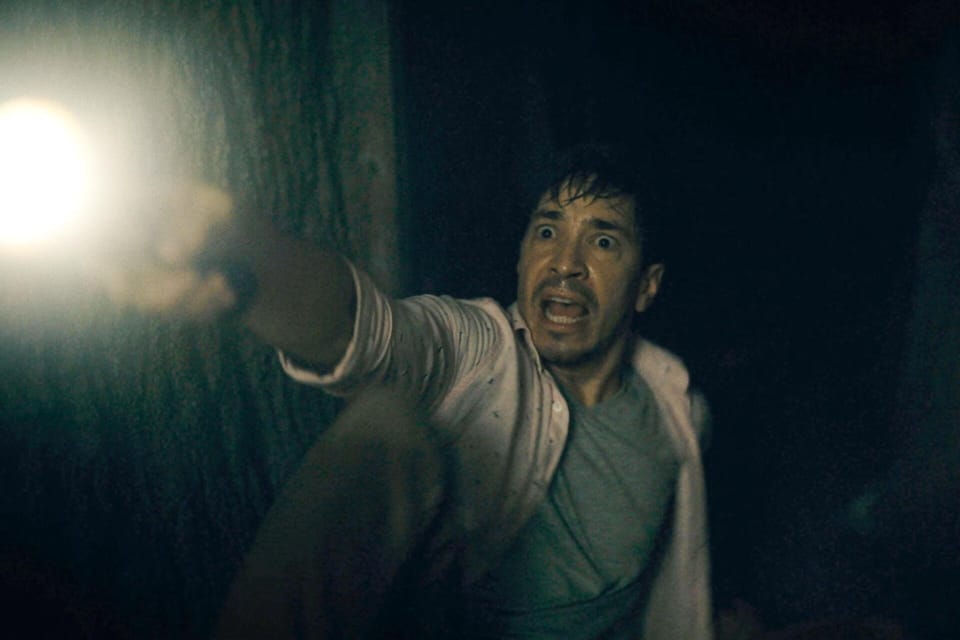

How does ALIENS get Ripley to agree to go back to the same planet where she found the alien that killed her entire crew?

How does the RAIDERS OF THE LOST ARK get Indiana Jones to go after the Ark? Okay, that one is easy. The Army approves the mission. Like I said, they aren't always difficult!

The point is, we didn't blink at any of these when we first saw the films. Yet they are true magic tricks of storytelling that got you to accept them as nothing but the inevitable choice of events and character.

My own challenging Act 1.

I have mentioned my project MOST WANTED before. It's one of my two case studies we examine in Idea To Outline.

The logline for Most Wanted:

A suburban family man suffering through a midlife crisis discovers his high school bully is on the police most wanted list and then drops everything in his life to hunt him down and capture him.

Hopefully that sounds fun.

One of the structural challenges here was to get this guy to decide to do this at the end of Act 1.

If he's a cop or a tough guy of any kind, it's not a challenge.

But that's not the fun of this piece. The fun here is that he is an emotionally desperate idiot who ventures into a world he has no business being.

I spend the first 10 pages setting up the bad guy and "A suburban family man suffering through a midlife crisis."

He hates his job. He's done nothing with his life. His son is being bullied at school. He thinks he's a failure.

The inciting incident is when he discovers his old bully is a fugitive.

So far, the challenge is mainly how to do all of this in a fun way that is enjoyable on its own and sets the vibe of the story.

But now I have 15 pages tops to get him on his quest.

This is sequence 2, the "What now?" sequence. Blake Snyder calls it the Debate section, which is another great term.

But both terms are misleading. Yes, the character and the audience are under the illusion that the character is trying to decide what to do next.

In reality, we are going through the sequence trying to convince the audience to believe the decision that launches us into Act 2.

This means we usually have to exhaust options.

The more suspension of disbelief required for this choice, the less of that we want to ask for. We really want to work on the emotional truth of this.

We can suspend our disbelief that Elle is accepted into Harvard Law; we cannot suspend our disbelief that she chooses to apply and go. We must believe that on its own.

In MOST WANTED, why doesn't Jay, our protagonist, just leave it to the police to handle it? What can he possibly do that they cannot?

Why does he choose to do this on his own?

If I can't answer this, this story flops before it gets out of Act 1.

So, in the outlining phase, I concoct that Jay has some information that might help the police (what he has that they don't), and he takes it to them so they can use it.

But they blow him off! His information seems pretty random, and they don't take him seriously. He fails.

The intent here was, "If they won't do it, I will."

But it just didn't work. I still didn't believe it. And if I am not believing, there is no way the audience will.

I could have created events that threatened him.

But once I explored those options, I realized it took away some of the fun. Much of the fun of this story is how crazy a choice this is.

But it still has to be motivated.

When physical motivation isn't there, look to emotional motivation.

And that's where I found it. I needed that extra kick to get Jay to do this stupid thing, and the answer was already there.

It was just in the wrong place.

I initially outlined Jay finding out his own son was being bullied in Sequence 1. But if I moved it into Sequence 2 AFTER the police mock him, I could fuel his anger at his own bully and all the bullies of the world just enough to start his engine.

And it worked.

I sold the script; we have a green-light director, and we are out to cast. No one has ever questioned this character's decision to do this remarkably stupid thing.

Yet it was one of the most challenging things to get right.

The inciting incident is an event.

It is something that happens TO the protagonist.

It knocks them out of their ordinary world and hurls them towards Act 2.

But the Act 1 break is a DECISION the protagonist makes. They must make that choice even if it's just accepting their new reality.

Because once they accept it, they must deal with it.

The easiest way to pull narrative momentum from the structure itself is to tie the dramatic question to the protagonist's want.

This is formed when the protagonist decides, "This is how I am going to deal with this problem."

And if the audience doesn't believe it, they're pulling the cord on the bus and getting off.

I am teaching a live workshop.

My friends at Pipeline Artist are hosting a symposium taught by yours truly on "Elevating Story Concepts."

If you've been considering taking a course with me but haven't yet pulled the trigger, this could be a good time. It's not too expensive, only $37, and it will be an excellent introduction to what I do.