The narrative point of view.

Like everything else, POV is a choice, and the most common mistake writers make is not making one.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

We’ve discussed the importance of a scene’s point of view many times in the weekly email. It was a prominent part of “The Scene’s Intention” just last month.

We have not yet discussed, however, the narrative POV. That is, what is the point of view throughout the movie?

Point of view dominates our narrative experience.

Newer writers will likely have a gut feeling about this; after all, they have been told stories their whole life. They have read books and watched movies, so they know the language of storytelling.

But they may not have consciously identified it yet, so their use of it is inconsistent.

In short, the immediate point of view is whose experience we share in a scene. The narrative point of view is whose experience we share over the entire narrative.

Narrative POV can be:

- A single point of view. That is, the same character’s POV from beginning to end.

- Multiple points of view that still tell one singular story.

- Ensemble point of view. This is multiple points of view for multiple stories within one narrative.

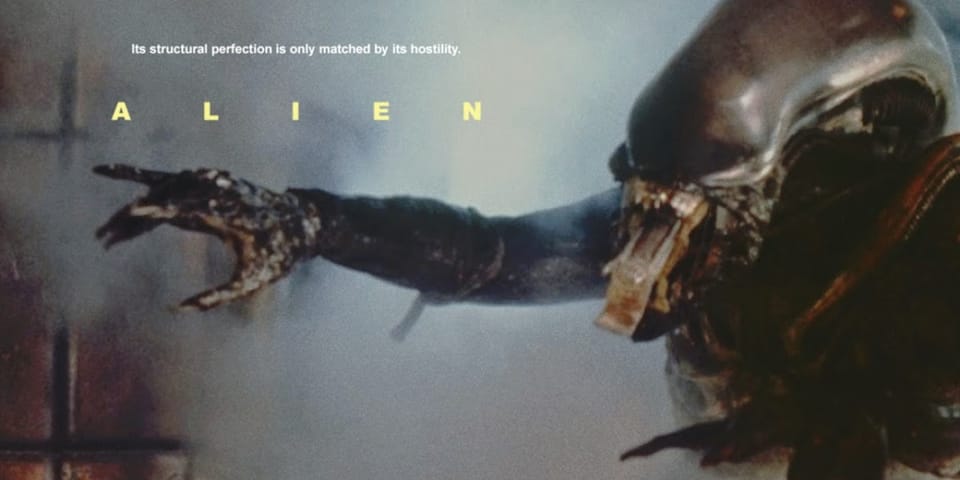

- A shifting point of view. This is when we start with one POV and then shift entirely to someone else's. PSYCHO is the most famous example.

Point of view is vital for information.

It dictates who we share information with, who we know more than, who we know less than, and how the storyteller uses that for dramatic effect.

It dictates who we identify with and root for.

Are we viewing the scene from an editorial point of view, or as an objective observer? How does this affect our emotional reaction?

Point of view also provides consistency in a piece's flow and rhythm.

This is the most overlooked aspect.

Once we get into a pattern of who we are sharing POV with, it is extremely disruptive to change it.

While you can certainly use this disruption to deliberately destabilize the audience, it more commonly feels like the storyteller has misstepped, and the audience loses trust in them.

Like everything, POV is a choice.

And the most consistent mistake writers make is not making a choice.

They may have a POV in one scene but not the other, suggesting the first was a mistake. Or they mix them up without realizing the cost.

Do not mix it up for plot purposes.

This may feel like an easy solution when we want to give the audience information, but it’s impossible to do so from the primary POV.

For example, we want to show how the bad guys found the protagonist!

The temptation is to cut to a scene with the bad guys that shows this very thing. It would build tension, right? We know the bad guys are closing in, and the protagonist doesn’t.

This is fine if the story has already established multiple points of view, but if it hasn’t… It’s best to find a more creative way.

Why?

Because that little bit of information is unlikely to be worth the disruption of suddenly shifting a POV late. It is likely better for the audience to discover how the bad guys found the protagonist as the protagonist does.

Intellectual reasons are not enough.

Shifting the POV to actually change our protagonist has tempted every writer since PSYCHO.

In PSYCHO, not only is the protagonist murdered 45 minutes into the film, the story abandons its old narrative, begins a new one, shifts to the POV of the person trying to cover up the murder to protect his mother, and then shifts to the victim’s sister, a private investigator, and finally settles again on the sister and the victim’s fiancé.

That’s a lot!

PSYCHO is a masterpiece, and it’s tempting to want to pull off that magic trick ourselves.

But it is not as easy as it looks.

Take heed of the audience’s emotional investment.

Shifting the POV comes at a cost.

This is an important concept that too many storytellers lose track of.

Every moment the audience spends caring about an outcome, they are making an emotional investment.

The longer they care about something, the greater their investment.

One of my favorite filmmakers, James L. Brooks, has a new movie out called ELLA McCAY.

Brooks has mostly lost interest in story structure over the last 20 years, and his films show it. Now, for me, anyone who gives us BROADCAST NEWS can do whatever he wants. I will watch and enjoy.

That said, each film survives on its own. And in ELLA McCAY, we get Ella’s POV for the first 70 minutes and then shift to her brother’s for 15 minutes on an entirely different subplot, and it’s frustrating because we have no investment in this storyline!

We just want to get back to Ella’s story! It is an odd misstep by one of our finest filmmakers.

This example is just a temporary shift. Imagine what it’s like if you remove the main POV entirely!

When you yank the rug out from under the audience by eliminating the POV they have invested in, their investment unsurprisingly plummets.

They could walk away at that point and be absolutely fine. In fact, part of them wants to because they feel betrayed by the storyteller.

This is one reason why Norman Bates's transitional POV is so important. It gives us an immediate thing to care about before shifting to the sister looking for Marion. It gets us reinvested before we give up entirely.

Too often, storytellers see this as an intellectual exercise.

It makes them feel smart to ambush the audience like that. They are so delighted by the upheaval they cause, they forget to emotionally satisfy the people watching!

This is the case with THE PERFECT GETAWAY and THE RIP.

To be clear, I enjoyed both movies, but their shifting POVs come at the cost of emotional investment.

I’ll focus on THE PERFECT GETAWAY.

It’s 17 years old and the far more extreme version. THE RIP was released on Netflix a few weeks ago, and it’s worth watching. I don’t want to get into any spoilers for THE RIP.

Written by the excellent David Twohy (who not only beat me out to rewrite PITCH BLACK but ended up directing it and got himself a franchise!), THE PERFECT GETAWAY focuses on a couple taking a long hike with another couple they just met.

They begin to suspect this other couple are the psychos on the news wanted for murder.

I am literally just realizing as I write this that “the perfect getaway” works both ways. The couple on vacation and the couple escaping their crime.

It took me 17 years to figure that out. Please keep reading and trusting me despite this.

SPOILERS AHEAD

The big twist of the film is that the protagonists we have been following are the psychos! The other couple, who we thought were the psychos, are just normal folks on vacation.

The third act is about the people we thought were our protagonists trying to kill our new protagonists.

It’s an extremely fun twist.

The problem with the twist is that it essentially ends everything. There is no more fun to be had!

We enter the third act, and not only is our emotional investment reset to zero, but it may even be less than that! We are asked to root for someone we have invested time in as the antagonist, and then to root for the defeat of someone we were empathizing with.

We simply do not have the emotional investment to sustain a third act with no more surprises left.

END OF SPOILERS

It’s a fun and clever experiment that doesn’t quite work.

Don’t get me wrong, I am so glad they took that swing, and I have no doubt they had a blast doing it.

But it is intellectually exciting, rather than emotionally satisfying.

And this is the trap that writers, including myself, will fall into.

It is always worth remembering: If it works intellectually yet doesn’t work emotionally, it doesn’t work at all.

Maintaining point of view is usually pretty simple.

This is because 90% of the time, the job is to remain consistent.

Whoever’s POV you’re going to share with an audience, do so within Act 1.

If you add an additional POV after Act 1, know exactly why you’re doing it.

Know what you gain, understand what you lose, and be sure it’s a net benefit.

Convenience is not enough here. Playing with the rhythm of POV is more disruptive than we think, and when done poorly, it drives a wedge between audience and storyteller.

There is a scene near the end of RETURN OF THE LIVING DEAD with a completely different POV than the rest of the film.

A military general gets a call in the middle of the night and approves a nuclear strike.

We spend the entire movie in and around this cemetery, and suddenly go somewhere else at the last minute! It's weird and unsettling. But “unsettling” is fine for this film! It heightens the stakes and underscores the characters' absolute helplessness.

In short, it works.

So again, there are no 100% rules. It’s just making each choice a conscious one and knowing your intention.

The major shift in POV cannot be the only attraction.

The stories that completely change the POV and still work as stories are those that still have more story to tell.

Even though PSYCHO is best known for killing its protagonist early in the film, an enthralling mystery remains. Will justice be served? Will Norman be able to protect his mother? If his mother is dead, who killed Marion?

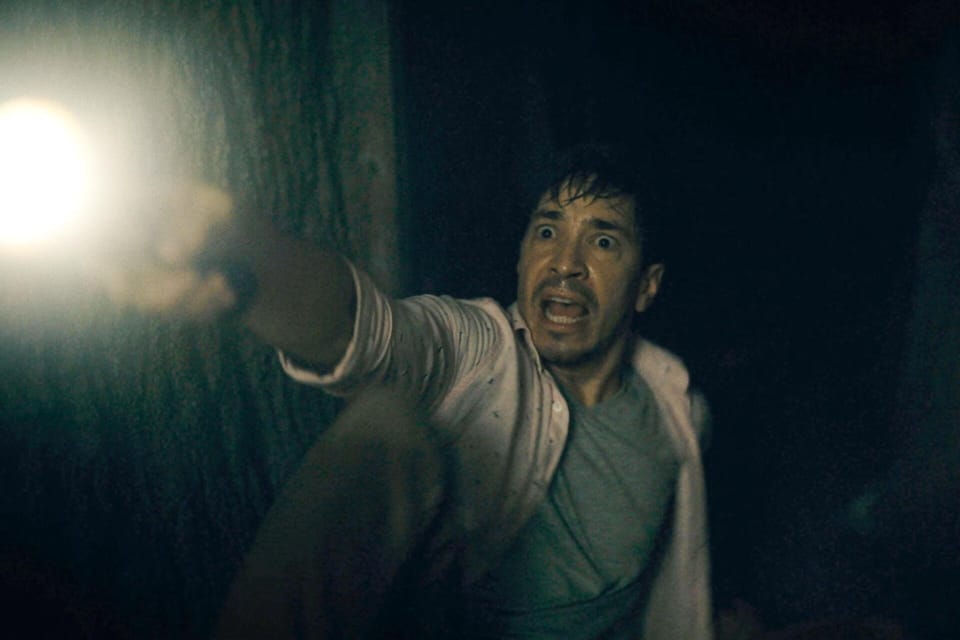

BARBARIAN shifts its POV near the midpoint and, in doing so, reveals it’s telling a different story than we thought! But plenty of mystery remains! What is down below? Where did it come from? The movie continues to offer more surprises AFTER the shift.

In WAVES, an excellent character drama, we never see the first protagonist again after the midpoint; instead, we get a whole new protagonist: his sister.

But the movie is actually two different stories around a tragic event. Before and after. The first story ends after the awful event, and that’s when the new story begins. His story, the first, is a tragedy, and her story, the second, is one of forgiveness and hope.

In each of these cases, the transfer of POV was part of the narrative, not the only thing that made the story worth telling.

Stories that shift POV as the big thing of value cannot stand on their own.

I spent years trying to get my POV-shifting screenplay off the ground.

It was called DOUBLE IDENTITY, and the protagonist was murdered 30 minutes in. I loved that screenplay, and no matter how many people passed, I kept thinking, “They don’t get it.”

It was only years later that I realized the problem with the screenplay was that the most interesting thing in the whole script happens on page 30!

It never got more interesting than that!

Point of view is a tool.

But it comes with a cost. The cost is so high that when we violate it, and it actually works to our benefit, it appears like a magic trick that puts the storyteller’s skill up front.

This is sometimes a temptation too hard to resist.

But the disruption of POV cannot be a goal in itself.

Why?

Point of view remains a tool in our toolbox for telling a story. The choices we make with our POV either serve the story or they don’t.

And the story always comes first.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

Tom Vaughan

Tom VaughanWhen you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline