The magic of sequence throughlines.

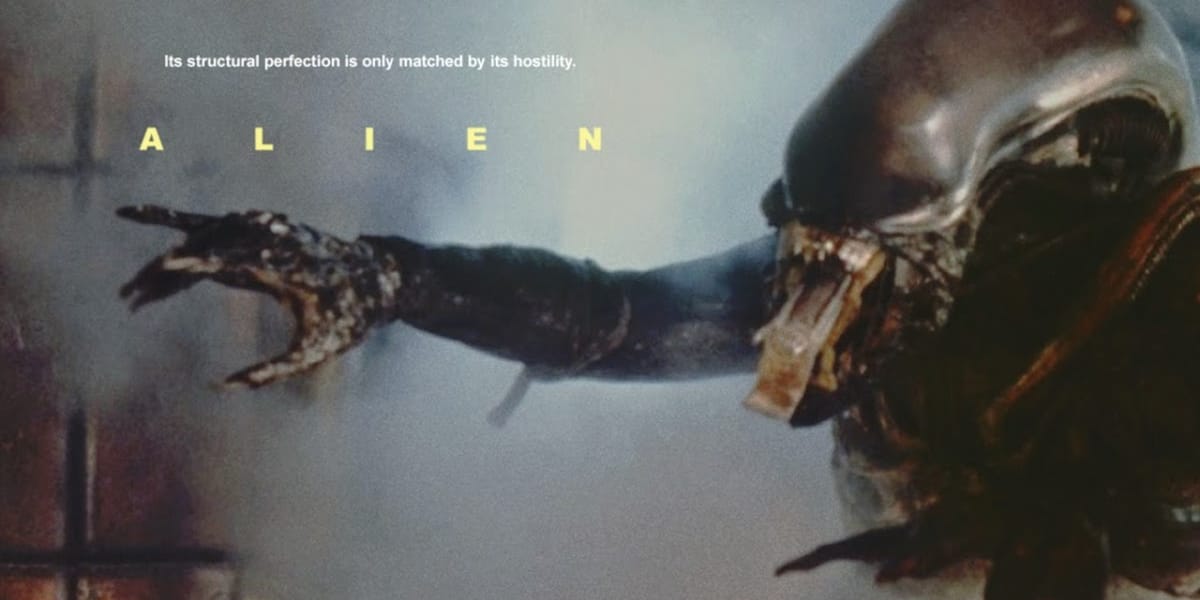

While ALIEN was not written in 8 sequences, it is a superb example of the 8-sequence approach.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

We broke down ALIEN in one of my UH classes a few weeks back. A few of the students have seen it already, but one of the joys of teaching at a university is introducing young adults to the classics.

While it is odd referring to the movies I grew up with as the classics, ALIEN is the equivalent of a movie from 1944 when I was college age.

Yikes!

There is no telling how many times I’ve seen this film. I lost count 30+ years ago. But it’s been a while since I broke the sequence structure down.

And the sequence structure is impeccable.

This highlights one of the most important lessons of structure. A structure is not impeccable because of how it is structured; it is impeccable because of the effect that structure has on the audience.

The only things we care about are narrative momentum and emotional resonance.

ALIEN is a superb example of the 8-sequence approach.

The strength of narrative throughlines to push a story forward is in full display.

Yet, ALIEN was not consciously written in 8 sequences, or 4 acts for that matter, or even 3!

The late, great screenwriter Dan O’Bannon knew little about structure when he wrote ALIEN!

His later book, Guide to Screenplay Structure, is as much a diary of him trying to figure out story structure as it is anything else.

Even as late as 2008, he thought the chest-burster scene was the end of Act 2, rather than the midpoint. O’Bannon makes no mention of the midpoint in his book at all, something I consider of the utmost importance.

But his talent, genius, and influence are unquestioned—perhaps even more impressive in this context.

It just so happened that O’Bannon and Shusett (who he wrote it with), following their gut about narrative momentum and emotional resonance, produced a fantastic example of story structure.

His later search for a process was born from his desire to be more consistent and not have to work so damn hard to get it right.

Something many of us writers struggle with before we settle on a process of our own.

Two things stood out to me, watching ALIEN this time around:

Many refer to ALIEN as a slow burn.

Yet, the narrative momentum is anything but leisurely. No one is bored. No one takes their eyes off the screen. The film is nothing short of compelling from first frame to the last.

So why do we even bother calling it a slow burn?

Because it has a late inciting incident.

That’s pretty much it.

Late inciting incident = slow burn. Fine.

But if the inciting incident is so late, and this is such a slow burn, why does no one find the movie’s first act slow? We will discuss!

How and why are the 8 sequences so clear?

If O’Bannon knew nothing about structure, and Walter Hill & David Giler’s draft didn’t veer far from the structure, why is the structure so damn perfect?

Because everyone involved understood drama. And drama comes from:

- Someone wants something.

- That thing is hard to get.

- Something will happen if they fail.

If you put enough of those wants in the right order, you will get narrative momentum, and if you give them a resolution, you will have a story.

Do not ask the audience for their patience.

They’re not there for you; your story is there for them.

Give them a reason to watch. Give them a question they need to see answered, a conflict they need to see resolved.

This is within the scene and the sequence, not just the entire screenplay.

- If the audience does not know what they’re waiting to see or what question they want answered or resolved, you are asking for their patience.

- If the only thing they care about will not be resolved for an hour, you are asking for their patience.

You must know what the audience is anticipating an answer to right now, in this scene.

What do the characters want? Why is it hard to get? What will happen if they fail?

ALIEN is considered a slow burn because the facehugger doesn’t show up until minute 34.

What’s the difference between “nothing happens for 34 minutes!” and “It’s a slow burn”?

Narrative momentum.

ALIEN has it. And a film "where nothing happens for 34 minutes!" does not.

I consider the facehugger attacking Kane’s face the inciting incident.

This is not universal by any means and is more about how my definition of inciting incident has changed over the years.

(Most would say when the crew finds out they have to investigate the SOS signal.)

But in any case, minute 34 is a long way into introducing the alien in a movie called ALIEN.

Yet, we are glued to the screen through every minute.

Three primary elements drive Act 1.

- We know what the characters want, and this want drives the narrative forward.

- This want is always driving us to an unknown that will be revealed.

- The characters react truthfully and emotionally to these events.

Narrative momentum and emotional resonance.

Act 1 of ALIEN

- The characters wake up. They are told they have received an SOS signal, and they must investigate.

- They want to land on the planet. This drives the action.

- We are curious ourselves about the SOS signal!

- They land on the planet and find the alien ship.

- They want to investigate. This drives the action.

- We are curious ourselves about what is in that ship!

- They find a field of eggs! Kane is attacked.

- They want to get Kane to safety.

- We want to know what that thing is, and will Kane be okay?

In each sequence, characters pursue their want, and this pursuit reveals new information, new obstacles, new reveals, and new emotions.

We barely notice it’s been 34 minutes at all. We just want to know more.

This same dynamic of decision, want, and outcome drives the entire structure.

8 wants. 8 sequences.

Nothing happens until someone wants something. -- Sydney Pollack

When breaking structures with students, professional writers I consult with, or even my own projects, there isn’t a more important question than “What does the character want?”

We need to know the want because the want drives the narrative.

The want is the river that keeps flowing, pushing the narrative around rocks and mountains, always driving to an objective.

Without the want, the narrative is a pond: static, going nowhere.

See each sequence as a throughline.

What is driving that sequence forward? In Mastering Structure, I show you the specific job of each sequence.

But ALIEN did this all naturally, just by pushing narrative momentum.

- An event happens.

- So they make a decision about what they will do about it.

- They pursue that want.

This carries them through the sequence, where the result is…

- An event happens.

- So they make a decision about what they will do about it.

- They pursue that want.

Let’s look at those sequences!

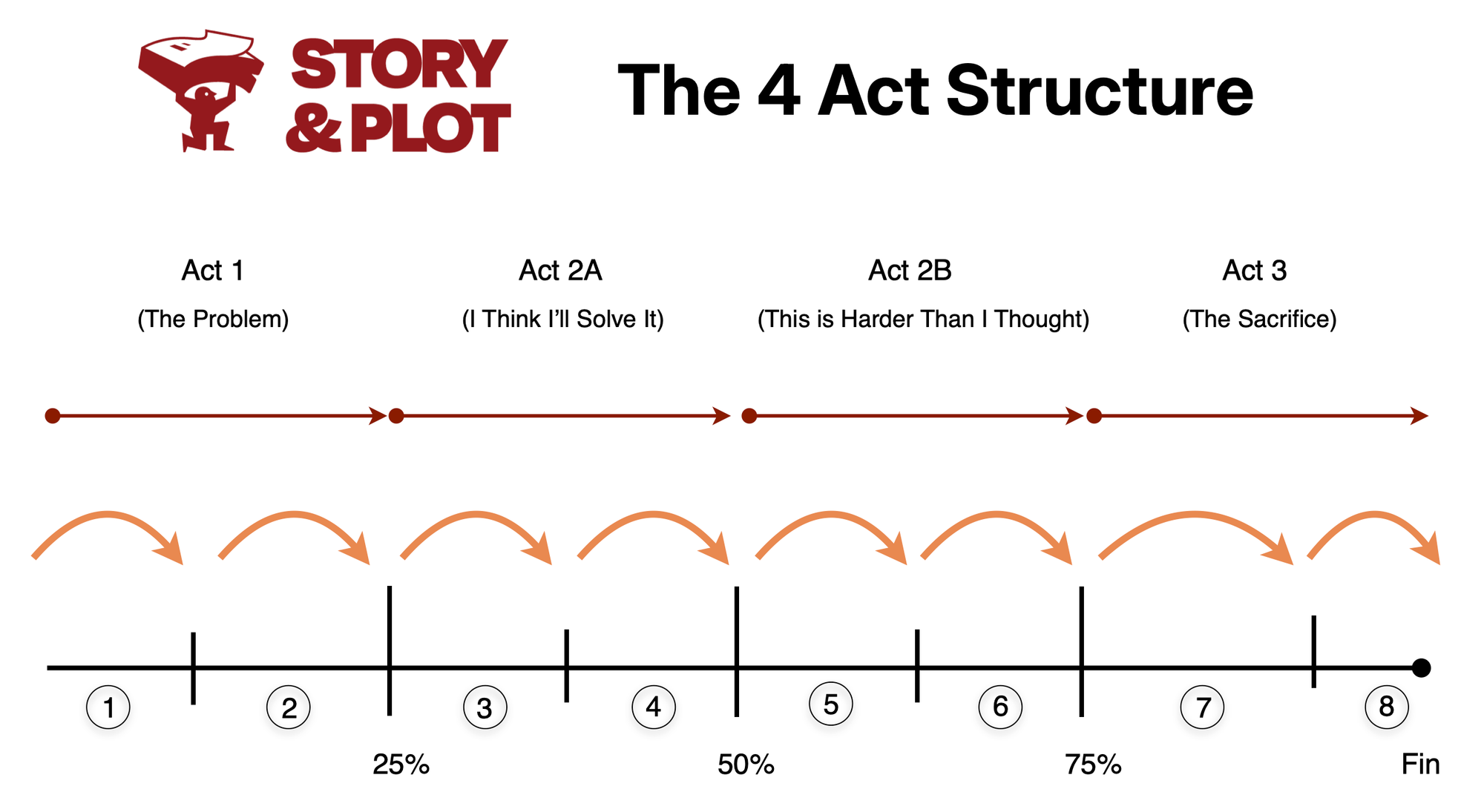

Here is a visual view:

We’ve already talked about Act 1, so let’s continue on.

Act 2A - Sequence 3.

An alien organism is now on board. They decide to try to remove the facehugger from Kane’s face. They cannot safely do so.

Until… the facehugger removes itself from Kane’s face.

Act 2A - Sequence 4.

Shocked that the immediate danger is gone, they decide to take off from the planet and calculate their way home. Kane even wakes up!

At the final supper before hypersleep – the chest-burster scene.

Act 2B - Sequence 5.

With an alien running freely on the ship, they decide to hunt down the alien. It kills two of them instead.

Including the ship’s captain, Dallas.

Act 2B - Sequence 6.

With Ripley now in charge, she decides to continue Dallas’ plan and to ask Mother, the ship’s AI, for help. She learns that the company does not care about the crew, only the alien. Ash tries to kill her.

Ash reveals to them they have no chance against the alien.

Act 3 - Sequence 7.

Knowing they have no chance, they decide to escape the ship on the life raft. The alien kills all but Ripley.

Act 3 - Sequence 8.

Having escaped into the raft, Ripley finds she is not alone and finally kills the alien. She signs off as Ripley, “Last survivor of the Nostromo.”

The want drives the action.

Each of these sequences leads to an event that springboards the narrative momentum.

Something changes. A decision is made about how to deal with it, creating a new immediate want.

It’s not rocket science.

The hard part is making it all work together in an emotionally truthful way so we, the audience, actually care about what happens next, and we find the culmination of it all emotionally satisfying.

Examine your own structure.

Whether you write in 5 acts, or 4, or 3; whether you write in 8 sequences or just throw stuff up against the wall and see what sticks.

Look at what your protagonist wants.

Are their more immediate wants changing and adjusting to events and pushing your narrative forward?

What is the throughline for each section of your story?

Does one exist? If not, is your story dragging because of it?

What reversals and reveals change a character’s tactics in pursuit of their want?

The simplest breakdown of structure I offer:

Act 1 - I have a problem. Act 2A - I think I’ll solve it. Act 2B - This is harder than I thought. Act 3 - The sacrifice is the solution.

Good structure is liberating.

It should give you the confidence on the big stuff so you can focus on the important stuff. We have learned quite a bit in the last 2,000 years about story structure.

You can do it the hard way, the (somewhat) easier way, you can do it like no one has ever done it before, or rely on the tried and true.

But in the end, the only thing that matters about structure is narrative momentum and emotional resonance.

If you maximize those two things, you are, by definition, well structured.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline