The habit of making choices.

Get into the habit of making choices, and you will get increasingly better with the choices you make.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

Perhaps the biggest difference between a good writer and one still working their way there is the confidence that comes across on the page.

A good writer tells the story.

The aspiring writer is searching for it. Almost apologizing for being there.

How can you tell the difference?

It’s pretty simple.

One makes choices. The other one doesn’t.

You exhibit confidence by executing your intention on the page. You execute your intention by knowing what you want in the moment.

You know what you want in the moment by making a choice.

You want to build confidence? Make clear, deliberate choices.

Why it’s essential.

I tell my students, whether in class, an online course, or in one-on-one coaching, one primary thing you never sacrifice is clarity of intent.

But the first step to that is the intent.

We tell our stories with purpose. There is life to them. If we want the reader to see and feel that life, we make choices.

We make a choice about the story, we make a choice of what we see on screen, and we make a choice about how we convey it on a page.

A director’s job.

Legendary playwright and screenwriter Tom Stoppard tells a story of working with Mike Nichols on his Broadway play THE REAL THING.

Someone asked Nichols about which of two chairs to use on stage and Nichols immediately chose the first one.

Stoppard asked what the difference was between them, and Nichols confided in him, “None. But it’s the director’s job to be decisive.”

You are directing on the page.

If you are going to telepathically deliver this movie into the reader’s mind, you have to direct it.

Be decisive.

Be specific.

Know what’s important and what isn’t.

Too often, we simply list action.

Our initial instinct is objectivity. We try to be an official recorder of events.

I think this is academia’s influence on us. Stay distant. Stay above it all.

We also write scared.

Our fear of criticism dominates. We can hear the note before we even write it. So we protect ourselves.

We refrain from making choices because we have been taught that making choices is where we get in trouble.

We can’t be wrong if we don’t take a stand, right?

We become a politician. Speaking a lot of words but somehow saying nothing.

But this lack of emotional commitment is a sure-fire recipe for boredom for the reader, who only wants to feel something.

The Jaws Exercise.

In my Introduction To Screenwriting class at the University of Houston, I ask my students to write the opening scenes of JAWS.

Having them write a scene for an already-produced movie gives us both a shared image of what they see in their heads.

Whenever we write a screenplay we make two choices.

- What happens on screen.

- How we convey it on the page.

The Jaws exercise takes care of #1 so the students can focus purely on #2.

And despite all the emotion present on the screen, their first instinct is to be dry, academic, and “just the facts.”

This isn’t a lack of talent. It’s a lack of confidence.

The confidence to make a choice about how we FEEL about what happens on screen (#1) and how that influences how we convey it on the page.

The choice is the emotion.

It’s not just what happens. That needs to be there and is vital, sure. We want the reader to visualize the movie.

But how does the reader FEEL about what they see?

This is the choice the director makes when they shoot and cut the film. But we get the first crack at it here on the page.

In JAWS, the young boy, Tom, approaches Chrissy. They chat and smile. She stands to her feet and races into the dunes. Tom follows.

That’s the action. Those are the facts.

But there are two aspects to this that the facts don’t always reveal.

- How does she race away?

- How do we feel about it?

She could run away because Tom creeps her out. They could be brother and sister fighting. He could be telling her bad news and she tears to her car to go home.

This is the easier one and few would forget this detail.

In this case, Tom introduces himself. She runs away playfully, and Tom follows just as she wants him to.

Needless to say, we need to make that clear.

But that second part is the one we so often miss. How does the audience feel about it?

This isn’t random. We choose it. You choose it.

Jaws plays the optimism. This is young love, full of hope and all the joys of life.

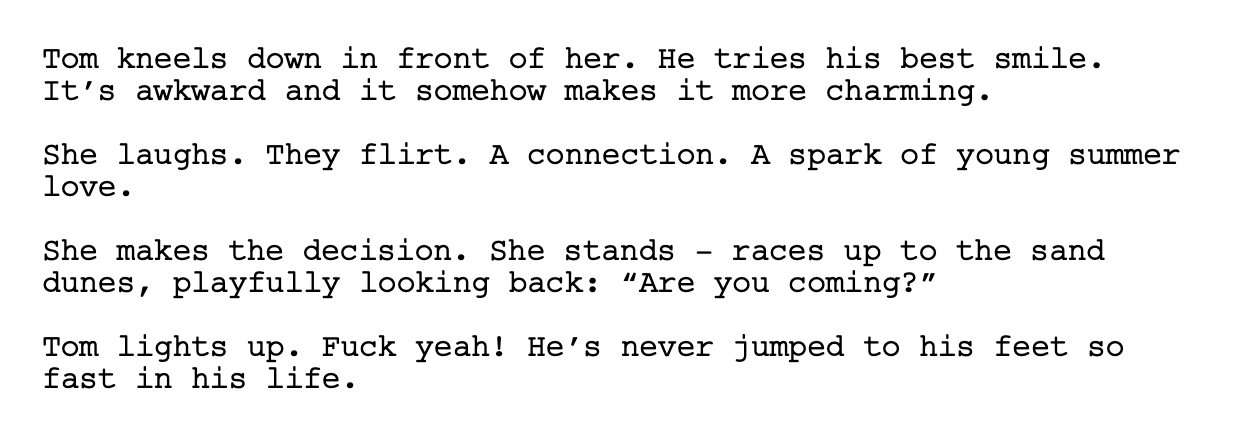

You could write it something like this:

This could be shorter, but I am making a point. This emotion opens the audience up for more pain when, moments later, Chrissy is attacked by the shark.

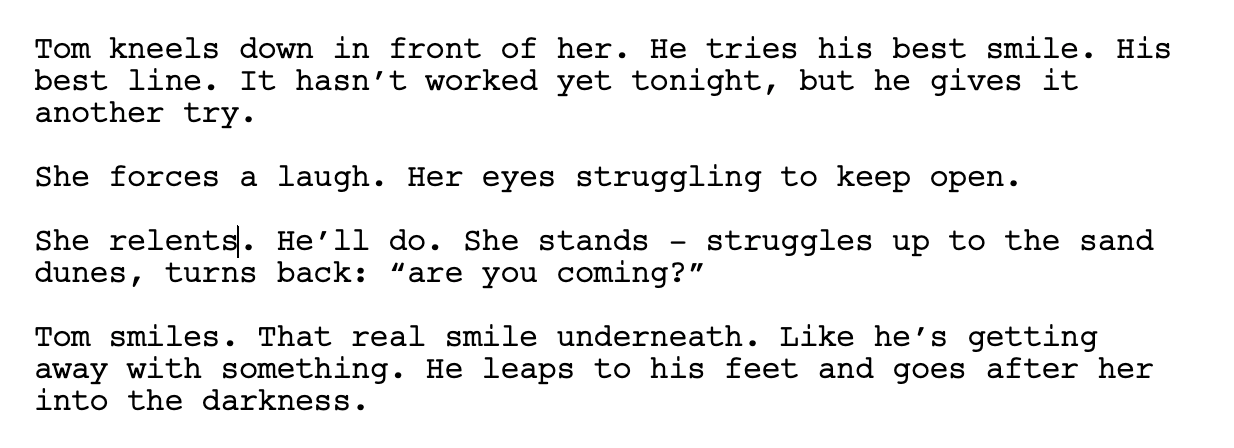

But in a different film, say Friday The 13th, we could play the feeling of dread that this is a terrible mistake that will lead them both to their death.

This is the exact same action but two entirely different emotions.

You don't need this much space to do it, either. Changing a single word can alter the meaning as well. Menacing. Stalk. Cold. Sinister.

Drop one of those, and the emotion shifts.

The small things add up.

Movies are an emotional delivery system. The audience wants to feel something. They want to feel something big.

Part of getting an audience emotionally invested is to make them feel something as soon as possible.

Just a quick laugh. A quick stir of empathy. Even something small.

Even if it’s just, “Awww. Young love,” or “I remember those days.”

Once you get the audience to feel one thing, getting them to feel the next thing is easier. Once you get them to feel the second thing, the third thing will come naturally.

And so on, and so on.

Now imagine getting a small micro-dose of emotion several times a page and how that opens the door to all kinds of bigger emotions later.

You can’t do this without making choices.

If someone gets out of bed, how do they do it? Do they leap? Crawl? Roll?

And then how do we feel about it? Sure, they're slow. But is it because they're lazy? Great! Is that charming? Sad? Or loathsome?

Or maybe it's because they worked all night? Do we feel bad for them? Or are we impressed by how hard they work for their family?

We can fill that moment with a quick, specific choice. It doesn't have to be a lot. The right verb or adjective is often enough. When the moment relies on it, you can stretch it further, like in the examples.

But make the choice.

Making choices is a habit.

For screenwriting, it’s one of the most important habits you can acquire.

Many people do it naturally. And we’ll call that a talent, for lack of a better word.

But others, like myself, have to learn to do it. We learn to do it by consciously forcing ourselves to do it until it becomes a habit.

Once it becomes a habit, we can tell everyone else it’s talent.

Making less-than-awesome choices is better than having no choices at all.

This is a hard lesson. Because we don’t want to feel wrong, we refrain. But making a choice — any choice, especially early on, is more important than making the “right” choice.

We have to acquire the habit.

The more choices you make, the better those choices become.

The better we get at knowing what we want to achieve and then achieving it, the more confidence we earn.

The more confidence we earn, the more we control the page.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline