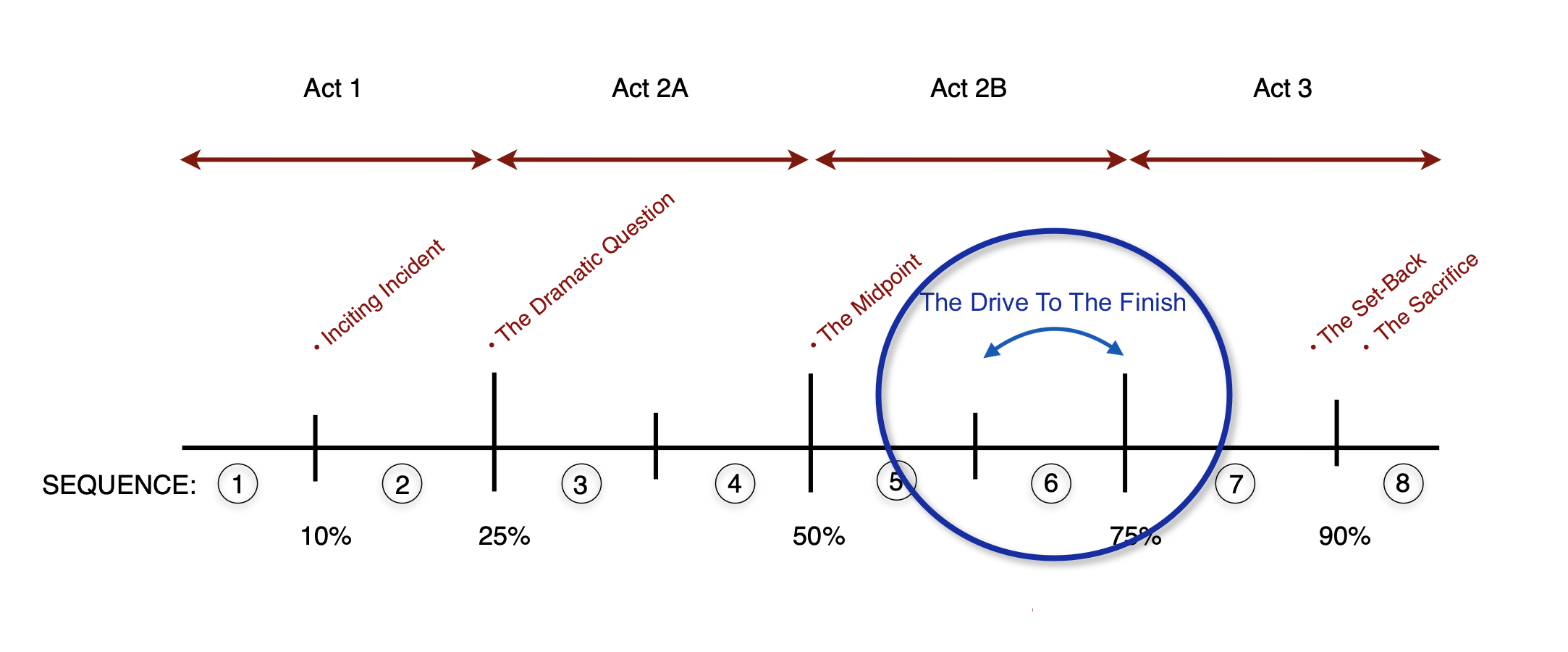

The Drive to the Finish

The decision that dictates Sequence 6: The Drive to the Finish is the midpoint.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

Act 2 is where you should be having fun. Act 2 is where the transformation happens—either the protagonist or those around them.

It is, by nature, the least static of the acts and will often require the most problem-solving.

Despite this (because of it?), Act 2 seems to give writers the most trouble.

It doesn't have to. Don't let it intimidate you.

Remember, Act 2 isn't really an act at all.

It's two acts combined. Act 2A and 2B, with each having a different role in your story.

Stop thinking of them as one unit. They are no more one unit than Act 1 and Act 3 are.

In addition, like all the acts, Act 2A and 2B are further divided into two sequences, with each sequence (3, 4, 5, 6) having a different job.

Today, however, I want to focus on Sequence 6.

This is the last sequence before Act 3. I call sequence 6 "The Drive To The Finish."

As you likely have figured out, I write in 8 sequences.

I discovered this when I was teaching back in 2003 or so. I didn't realize I was even doing it. I just recognized that the two parts of Act 2 were clearly split in half in both the movies I broke down and learned from and the movies I wrote.

I didn't have a name for them and I think one of my first students, John Conner, came up with the term "waypoints."

I kept teaching, I kept writing, and I kept learning, finally getting confident that there was a consistent way to approach these sequences that I could share with others.

Eventually, I ended up with 8 sequences (labeled 1-8) within the 4 Acts (1, 2A, 2B, and 3).

Each of these sequences and act has a job in your story.

Combine this with all the structural decisions that interlock and influence each other, and you have a guiding force in your narrative.

It doesn't dictate anything to you. But it does give you direction.

It frees you from the tyranny of infinite choices.

For years, I have described story structure as a crossword puzzle. Once you make one decision, you narrow your choices for the next one.

Which narrows your choices for the next one. And so on and so on.

The more decisions you make, the more inevitable the next one becomes.

The decision that dictates Sequence 6 is the midpoint.

This is what I mean by interlocking decisions. Sequence 6 does not exist in a vacuum. It is part of your story. These are not random events.

Sequence 6 is a result of what comes before it and creates what comes after it.

So instead of just thinking, "What could happen next?" We look at the midpoint for guidance.

Is the midpoint a victory or a defeat?

You have to go back a little bit to how I define a midpoint, but a big part of this story beat is whether it is a victory or a defeat for the protagonist.

Neither is permanent, of course, but it should feel like a major step forward or a major step back.

- In BRIDESMAIDS, Annie is "fired" from being the maid of honor. A defeat.

- In RATATOUILLE, Remy and Linguini are massive hits, the toast of the town. A victory.

- In SKYFALL, Bond captures Silva. A victory.

- In THE AVENGERS, the heliocarrier is attacked by the Chitauri. A defeat.

We use this to determine the emotional direction for Sequence 6 for our protagonist.

- If the midpoint is a victory for the protagonist, then it will be the antagonist who is gaining strength and has the initiative in Sequence 6.

- If the midpoint is a defeat for the protagonist, then it will be the protagonist who is gaining strength and has the initiative in Sequence 6.

This will give you the drive of the narrative.

This isn't some kind of written rule somewhere.

It is simply the nature of story and what holds our emotional attention.

No one wants to see the protagonist win from start to finish. Even Steven Seagal would have some setbacks in his movies, and I'm not sure he ever lost a fight!

Nor do we want to see a protagonist lose out of the gate and continue to lose until the end. Admittedly, however, there is a slight bit more room for this one, but the world can handle only so many REQUIEM FOR A DREAM and FUNNY GAMEs.

The yes-no nature of scenes is mimicked in the structure.

Back and forth, victory and defeat. Yes-No.

- In BRIDESMAIDS, Annie decides to change her life in Sequence 6, until she finds out Lillian is missing for the wedding, which launches her into Act 3.

- In RATATOUILLE, Sequence 6 begins with critic Anton Ego declaring that it is he who decides who is a great chef and he's coming to the restaurant that Saturday night. The friendship between Remy and Linguini falls apart just before the Saturday dinner, launching us into Act 3.

- In SKYFALL, Bond discovers in Sequence 6 that it was Silva's plan to be caught and Silva now has total control of the computers! Bond retreats to his childhood home to launch us into Act 3.

- In THE AVENGERS, with the Chitauri victorious and The Avengers spread out, they must lick their wounds and reunite to defend New York City for the final battle that launches us into Act 3.

How to execute this in your outline:

The key is to know where you are going. When I break my story, I make certain decisions first because so many other decisions are based on them.

First and foremost, 1) What is the story? and 2) What is the dramatic question?

If I know those, I can narrow my options and make decisions about the inciting incident, and the Act 2 break (the dramatic question).

Those are the easiest ones because the intention is built in from the story and the DQ.

I will almost always then make the following two choices:

- The general idea/thrust of Act 3.

- The midpoint.

From there, I have two options:

Option A - The pivot scene creates Sequence 6.

This is when I know what the low point of Sequence 5 (the pivot between Sequence 5 and 6) is going to look like. A big question for me is, "What is the worst thing that can happen to the protagonist?"

I usually look for something emotional here rather than, "They die."

In THE GOOD TEACHER, the mom is arrested and she loses her son to CPS.

Of course, severe physical stress is absolutely an option here, but I am usually looking for something a little more grueling.

The point here is that if 1) I know the end of Sequence 5 - the low point/pivot scene, 2) I know the beginning of Sequence 7, and 3) I know who has the initiative and is driving the sequence… I have narrowed Sequence 6 down to a very manageable number of fun options.

Option B - Sequence 6 creates the pivot scene.

This is less common, but it is for when 1) I know Act 3 and 2) I already know what the driving action of Sequence 6 is going to be.

If I know these two things, and I obviously know the midpoint, then I can connect the two sequences with a well-chosen low point at the end of Sequence 5.

Just remember —

Good story structure isn't what makes your screenwriting work.

It's what allows it to.

Good structure maximizes great scenes, engaging characters, and emotional moments.

You're not trying to be a genius here. You're just trying to put these things in the best position possible.

There are countless ways to do that.

If you get stuck, lean on a process.

Make true decisions.

There are usually two things holding you back in the process. The first is indecision, and the second is half-effort answers as if it's homework. Filling in the blank and getting it over with is the priority.

But the more serious and deliberate your early answers, the easier the later decisions get.

The less specific your decisions are, the less they guide you.

And soon, despite having written a whole screenplay, it appears as if you haven't made any decisions at all.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline