The most important part of Act 3.

The moment when a character earns ownership of their change by surrendering something they once valued but is no longer aligned with their new value system.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

The Sacrifice.

I have come to recognize the sacrifice as one of the most critical moments of any story. This moment doesn't have to be the funniest or scariest. It doesn't have to be a spectacle or a set piece. But when done well, it should be the most emotionally satisfying moment of the whole journey.

A better understanding of the sacrifice changed my writing.

I always knew a character had to change, but my early implementation was terrible. It was change for the sake of change. I didn't realize that the transformation was the story itself. I was structuring out the plot and adding a change to the protagonist later, like a throw-away line at the end of a scene.

No wonder my earlier work fell flat.

It was only when I started writing FOR the transformation that my work began to resonate. With that growth, I came to see the importance of sacrifice.

Definitions

The Sacrifice: The moment when a character, most often the protagonist, earns ownership of their change by surrendering something they once valued but is no longer aligned with their new value system.

The realization at the end of Act 2B is just an internal recognition. It's a desire. But with the sacrifice, they then own their transformation. And with the sacrifice, they kill off their old self.

A legendary example is Luke Skywalker turning off the targeting computer to solidify his journey to become a Jedi.

In SEVEN, Detective Mills executes the killer, solidifying his tragic transformation into someone new.

BARBIE decides that she doesn't want her life to go back to how it was and chooses to become human and, by its nature, mortal.

The 4-Act Structure.

You may have seen me post about this 4-act structure breakdown on social media. It's a quick way to visualize a direction and purpose for each act.

- Act 1: I have a problem.

- Act 2A: I think I'll solve it.

- Act 2B: This is harder than I thought

- Act 3: The sacrifice

The sacrifice isn't a sequence or scene but a moment. Yet the entire act is named after it. That's how important it is.

The ideal structure of the sacrifice.

My writing evolved into eight sequences about ten years into my career, and I find it the simplest and most consistent way to structure a story. It's how I write and teach. Of course, there are many ways to structure a story, so look at this as an example.

In this ideal framework, the sacrifice is a response to the setback at the end of Sequence 7. Things have gone wrong, and whatever plan the protagonist had is not working.

They must improvise and adapt; the sacrifice is how they answer the dramatic question to the audience's satisfaction.

For example, in THE AVENGERS, after being overmatched by the second wave of Chitauri invaders, the most selfish Avenger, Tony Stark, blows up the portal with a nuclear weapon, seemingly killing himself to benefit others.

The sacrifice completes the character change for whichever character performs it.

Sounds easy, right?

But here are a few things to think about:

The sacrifice signifies change.

This is the source of the audience's emotional response. The sacrifice is not just a plot device but the final moment of character growth.

The sacrifice is a choice the character makes that they would not have made in Act 1.

In Act 1, Barbie wants everything perfect again. In Act 3, she chooses to be an imperfect human.

In TITANIC, Jack is a lone wanderer. In Act 3, he dies so another can live.

In BRIDESMAIDS, Annie wants everything to remain the same. In Act 3, she actively pursues her friends happiness knowing her life will change because of it.

If the sacrifice in Act 3 is something the character would do in Act 1, the act will mean very little to the audience.

The best sacrifices solve the problem.

Like THE AVENGERS example above, you will maximize your emotional response if the sacrifice resolves the dramatic question. It just doesn't have the same impact if it isn't the climax.

BACK TO THE FUTURE 3 features a terrible sacrifice, with Marty refusing to get baited into a drag race when he was called a chicken. The story was over, and it felt tacked on. It didn't work.

ARGO attempts something similar by having Mendez go home to his family. But the story is over, and, like Marty, Mendez isn't a transformational character.

You will get the most out of the sacrifice if it simultaneously solves both the external problem (the dramatic question) and the internal problem (the transformation).

The great Michael Arndt would argue that it should also resolve the "philosophical stakes" at that moment. While this is 100% true, I believe the transformation should embody the philosophical (thematic) stakes, so for me, they are the same anyway.

This is a variance in verbiage and not in substance.

Make it emotional.

This is what it is all about. We want to evoke an emotional response from the audience.

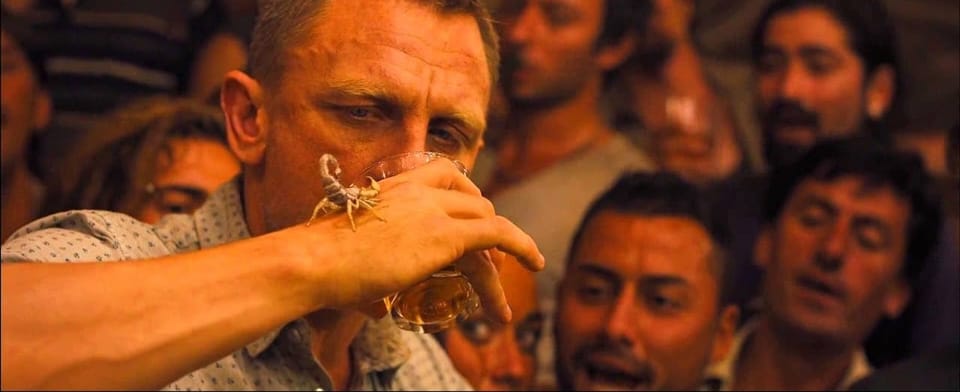

I often use WORLD WAR Z to introduce story structure because it is a simple, clean, sequence-based structure. No matter how many times I watch it, my favorite moment remains Brad Pitt's character injecting himself with an unknown disease, having no idea if it will kill him or not.

He does this for his family and the world and it moves me every time!

It can be the sacrifice that moves the audience, like Jack giving Rose the raft in TITANIC, or the result, like Luke blowing up the Death Star. But one of the two (or both) should move the audience according to the tone, genre, and parameters you've established for your story.

It's not always the protagonist.

Those who change complete the change through sacrifice.

So, if your story is about a protagonist who remains steadfast and changes those around them, the change of those around them should be solidified by sacrifice.

In RATATOUILLE, one of my favorite examples of this kind of story, Remy's dad Django, Linguini, Collette, and the Critic Ego perform an action in Act 3 that they would never have done in Act 1.

- Django helps his son cook for the humans.

- Linguini confesses he is not the real chef and helps as a waiter.

- Collette comes back to help after learning a rat is the cook.

- Ego gives a rave review of the food, knowing that a rat cooked it.

The sacrifice is about emotional satisfaction.

Our goal with every story is to answer the dramatic question to the audience's satisfaction. This may mean victory or defeat, a happy or sad ending. Comedy or tragedy.

Whatever it is, in the end, what matters is the audience's emotional satisfaction.

Nailing the sacrifice is one of the biggest contributors to this.

That's a wrap for this week!

I am nearing the one-year anniversary of the Story and Plot Weekly Email.

I aim to hit 5,0000 subscribers, 9,000 Twitter followers, and 2,000 LinkedIn followers by April 12th.

Does any of those numbers really matter? Nah. Not really. The depth of the content is what counts, and the relationship I have with readers. But...

Those numbers do help spread the word. And goals are fun.

So, if you're into it, please share my social media accounts and this post and introduce the best screenwriting blog out there to someone who might enjoy it.

You can find me on these respective platforms here:

See you next week!

Tom

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline