The 3-Part Act 1 and the Inciting Incident.

Sometimes the needs of Act 1 do not lend themselves to an early inciting incident. For those unique stories, you have the 3-Part Act 1.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

We started the Story and Plot Pro sessions last week, selling out both the Tuesday and Saturday sessions.

Pro is fun for me because it gets me away from lecturing and allows me to focus more on one-on-one development from the ground up, all while building a community of screenwriters.

More and more of my teaching energy (and some of my writing energy) will be going there.

Members offered initial ideas this week, and discussions on defining our stories and establishing the dramatic questions emerged.

I was reminded of the usefulness of the 3-Part Act 1.

It’s actually quite common in movies, but we too often forget to utilize it in our own screenplays.

The 3-Part Act 1 has a late inciting incident.

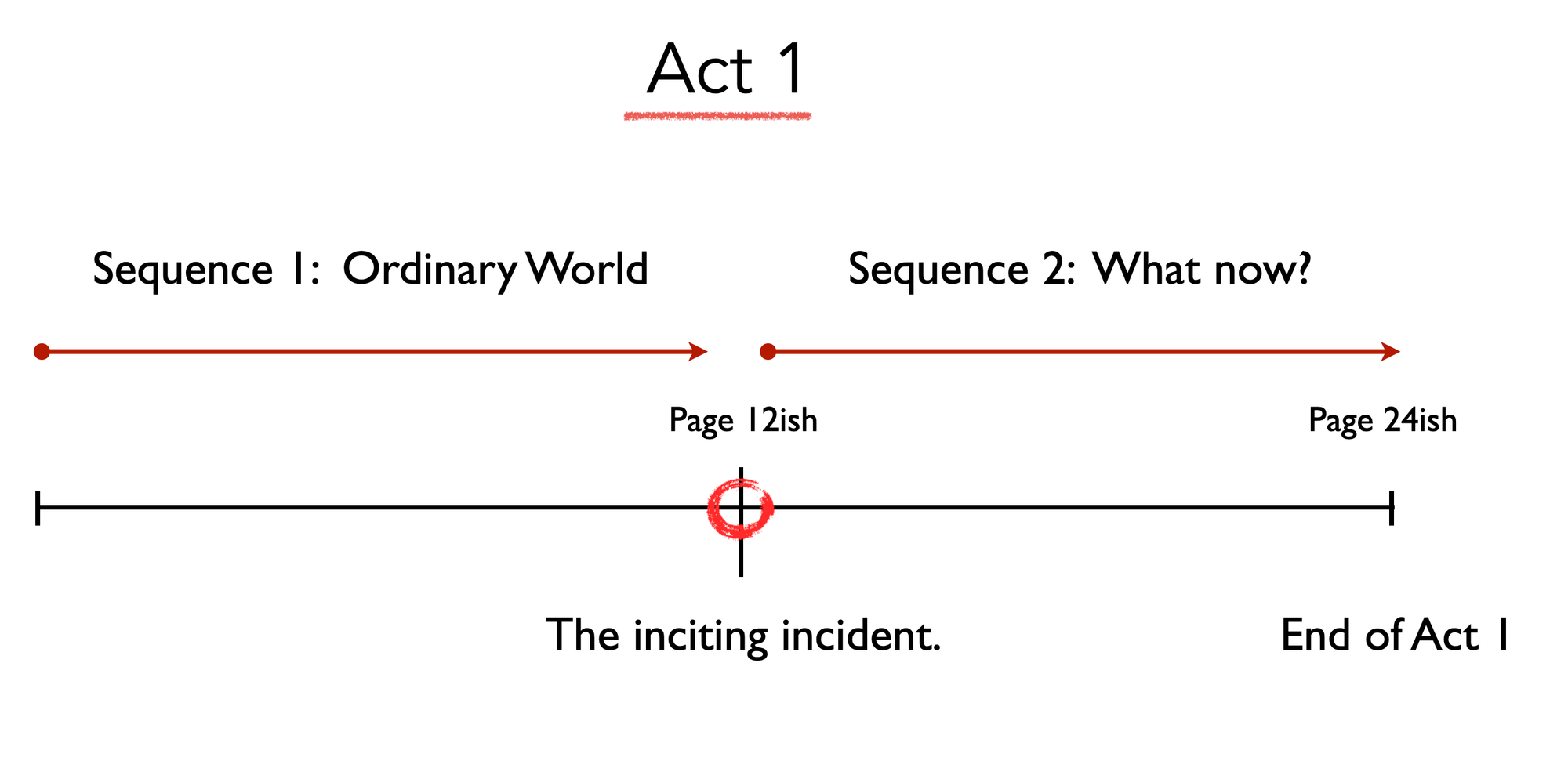

You have undoubtedly been told that there is a proper place for the inciting incident in your story.

You’ve probably heard something like page 12.

Then you likely heard someone screaming about how that sort of thinking is antithetical to artistic expression, that there are no rules, and so on and so on.

As it is with so many of these discussions, they’re both kind of right.

There are countless ways to do this. Do what works.

When someone calls something a screenwriting “rule,” it’s usually because they know that they should do something, but they don’t understand the “why.”

If they knew the why, they would know when not to do it, and when you know when not to do it, you know it’s not a rule.

Don't get me wrong, it’s smart to have your inciting incident around page 12.

This guidance stems from the fact that part of the inciting incident’s job is narrative momentum, and if you wait too long, narrative momentum suffers.

But that’s not the inciting incident’s only job.

The inciting incident has three jobs.

- Knock the protagonist out of their ordinary world.

- Lead us to the dramatic question.

- Give us narrative momentum.

It also has to work seamlessly with everything else in Act 1.

And there is a lot going on in Act 1.

It is deceptively complicated. You must establish character, genre, tone, the ordinary world, and control how the audience feels about it.

Then you want to deliver some reversals, and often a character choice that launches us into the rest of the story.

It’s a lot.

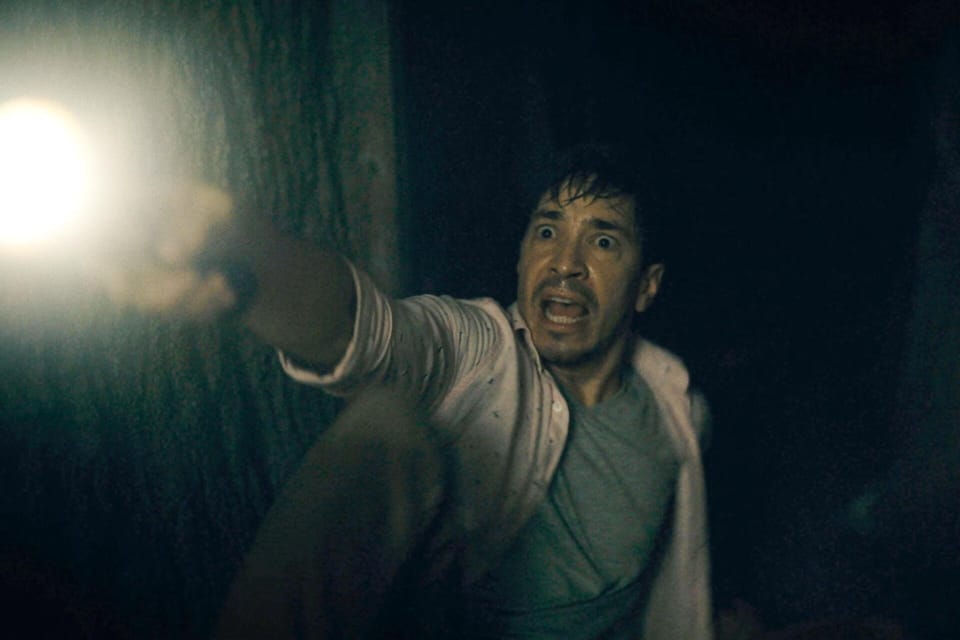

When it’s working as normal and everything is simple, a traditional structure will look like this:

But sometimes, the needs of everything in Act 1 may not lend themselves to an inciting incident that accomplishes all three of its own responsibilities.

For those unique stories, you have the 3-Part Act 1.

The 3-Part Act 1 divides the inciting incident’s jobs.

It allocates narrative momentum or knocking the protagonist out of their ordinary world to a different event, preserving the inciting incident for its primary responsibility: to set up the dramatic question.

I used to define the inciting incident as the event that knocks the protagonist out of their ordinary world.

And that is not wrong. That is how most do it.

However, as I was looking for unified processes that I could utilize in my own writing, I found that definition lacking and sometimes confusing.

So, for my writing, I look for an inciting incident that leads us to the dramatic question: What is the event that introduces the problem that must be solved?

This does not matter to an audience. They don’t care, nor should they.

But it’s not purely academic either, as I have written these definitions specifically to make my job easier.

For example:

For years, I pointed to the moment when Hans Gruber and his team emerge from the truck as the inciting incident for DIE HARD.

But it really can’t be. John McClane has no idea it’s happening. It’s not shattering his ordinary world, and it’s not leading us to his problem.

He is in Holly’s office making fists with his toes.

It’s not until almost 7 minutes later that Gruber’s team actually takes over the party, forcing McClane to react and make a choice.

That’s the inciting incident. 23 minutes in.

So, yes, of course, you can wait until page 23 for your inciting incident.

But 23 minutes is a long time. That’s a complete sitcom.

You need the equivalent moment of the terrorists (thieves) stepping out of the truck and giving the story narrative momentum.

McClane doesn’t know they’re there, but we do. And we are now anticipating a moment of conflict in the coming minutes.

You can even pull a LA CONFIDENTIAL or a GODFATHER and have an inciting incident over 30 minutes in!

But what is giving you dramatic momentum until then?

Don’t be afraid to separate the ordinary world from the inciting incident entirely.

That’s what RATATOUILLE does.

Like DIE HARD, I’ve changed my mind about what I think the inciting incident is in RATATOUILLE.

I used to identify Remy’s separation from his family as the inciting incident.

Why? Because that knocked Remy out of his ordinary world.

But this doesn’t lead us to his problem or his want. This is not a story about a rat trying to reunite with his family.

In fact, he is reunited with them around the midpoint, and they’re mostly an obstacle to the primary dramatic question, “Will Remy, a rat, prove he is a truly great chef?”

So what actually starts that adventure is when Remy falls into the restaurant kitchen at minute 21.

The 3-Part Act 1 is for when you need more time.

Brad Bird could have easily made Remy a rat living in a restaurant, and it would not have required so much plot to get him into that kitchen.

But that would have been a slightly different story. Remy would not have felt as isolated nor as FREE from his past identity. His family would be more conditioned to human interaction, and Paris would not have been as alien to Remy.

So Bird decided to separate Remy from his home first and then drop him into the kitchen.

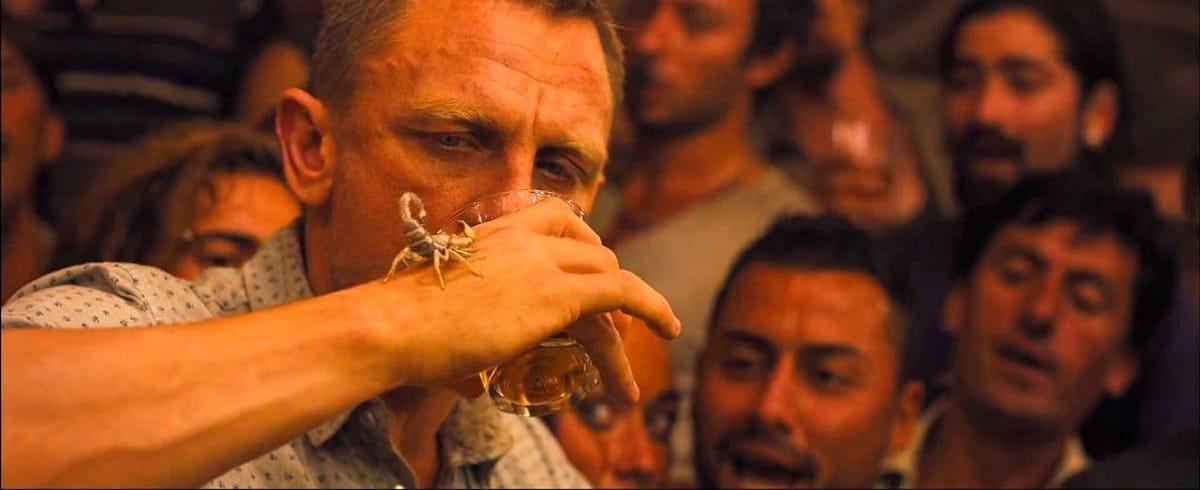

The inciting incident in SKYFALL is 24 minutes into the movie.

Of course, no one would have flinched if Bond got the mission at minute 12 and decided to save the world then and there.

But that’s not the story they wanted to tell. The ordinary world of SKYFALL is James Bond getting shot on M’s orders, falling off a bridge, and abandoned.

It turns out it is the same fate the antagonist received years earlier.

The next event of the story is an explosion destroying MI6, which kicks off the main narrative.

But that is not the inciting incident.

Sure, we get plenty of narrative momentum out of it, but Bond doesn’t. His world is still the same, off on a beach somewhere.

It’s Bond seeing the explosion on TV, which is our real inciting incident.

One far less exciting, but that’s our story. Bond, too old, ordered to be collateral damage by M, left for dead… This is what gave SKYFALL the emotional layers so many Bond films miss.

And they needed a little more time than usual to do it. But because the story had dramatic momentum from the first minute on, no one noticed a “late” inciting incident.

The 3-Part Act 1 should not be your first choice.

It’s a little more challenging, and there is a beauty in the simplicity of the first option: 1) Ordinary world, 2) Inciting incident, 3) Dramatic question.

It’s done for you! You just have to focus on great scenes! That’s the dream.

But some stories want more. Some stories need the protagonist out of their ordinary world before they can be introduced to their problem.

Some need to establish stronger relationships to get us invested, justify character choices, or deepen the emotional impact.

Whatever the reasons, whether it’s for story or plot, or both, have this option at the ready.

Do you geek out over structure like me?

Perhaps you simply want to improve your structure so you can write the screenplays you know you're capable of.

If you liked this week's email, you will love my course, Mastering Structure. There is no better screenwriting course out there, and it's guaranteed. Love it or your money back. Seriously.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline