Story vs Character Arc.

I haven't used the term "character arc" in decades.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

A few weeks back, I wrote about the screenplay I wrote that helped get my first agent, and how I tried to “copy” that screenplay for my follow-up. It failed.

It was insincere and cynical, and it was obvious.

Now, it was structured mechanically just fine. There was a (somewhat) interesting concept, and the set-pieces were fun. None of that is where that script fell apart.

Instead, it failed at the most basic level: the story.

As you probably know, I define Story as:

The transformational journey of a human being.

But I didn’t define it as such back then.

Like most, I lacked even a working definition of story! I thought of the whole thing as “the story.”

If you had asked me for a definition, I would have come up with something to describe what a story is, rather than what I do now, which is define each term in a way that helps me do my job.

My first (professional) script had a story.

The character started one way in Act 1, and Act 2 changed them. It changed them through a lot of cool action scenes, but those scenes were necessary to get him where he was in Act 3.

In Act 3, this transformation allowed him to solve his problem. Without the change, he would have failed. This change also gave him a comfort level with himself and his relationship that we wished for him.

The next one had a “Character Arc.”

It had a plot. Things happened. Some cool scenes. And at the end, the character was “different.”

The change was random, and it felt like just about anything would have made it happen. In addition, the change wasn’t required to solve his problem. It felt more like a lateral move than something they needed or that we wished for them!

I thought focusing on the plot would make it easier for me, but it was actually making it much harder.

This is the difference between a Story and a Character Arc.

And that’s why I no longer use that term and haven’t for decades.

The term’s existence suggests it is separate from the story. And too many treat it that way.

It’s something they tack on late in the process, sometimes even last!

And while this isn’t actually terminal, it puts an incredible burden on getting everything else right. You need a lot of luck and skill to get away with it, let alone pull it off well.

I lacked both of them at the time, and the screenplay didn’t work.

I have learned since then that I want to make choices that make an already difficult job easier, not more difficult.

Embedding the transformation into the narrative's DNA is one of those choices.

The story is the heart.

Story is about change. Something is different at the end than it was at the beginning.

Either the protagonist changes for the better, they change those around them, or it’s a tragedy, in which case, they change for the worse.

In all cases, the change takes center stage.

You’ve heard something described as the “heart of the story” before.

It’s important to understand that the story is the heart of everything else.

It’s what gives everything we witness an extra emotional boost.

And we are, at our core, an emotional delivery business.

This dynamic is obvious in smaller, more emotional character movies, but it’s also why some big-budget films stand out amongst their peers.

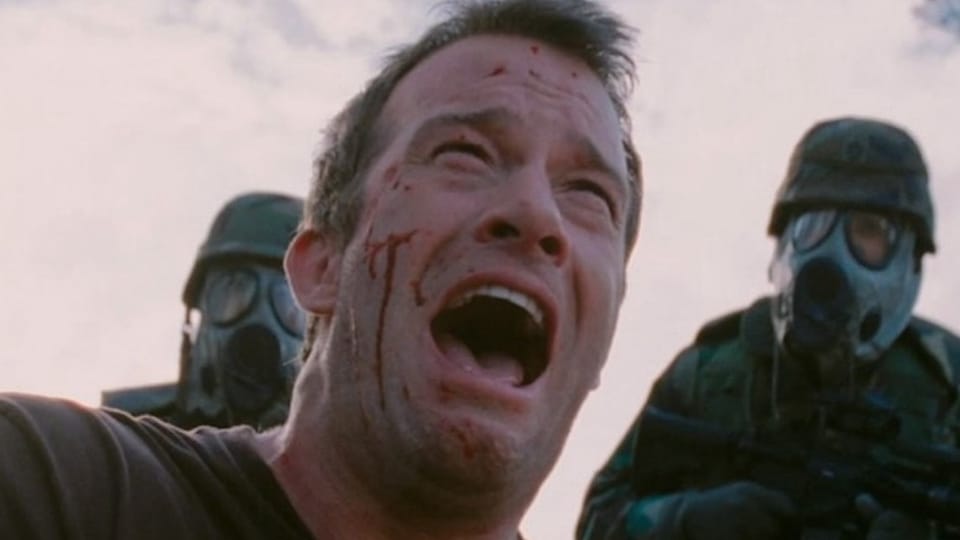

It’s why DIE HARD stands taller than all those other great 80s action films (and there are some great ones.)

It’s why the end of LA LA LAND is so much more memorable than the rest of the film.

It’s why the end of AVENGERS: ENDGAME is unlikely to be topped by another comic book movie, and DOOMSDAY already feels like a disappointment for trying.

It’s why Jack’s sacrifice in TITANIC moves us so much.

The transformation or the tragic lack of it tells us what the story is about.

There is no theme without it, no depth, and while not impossible, the emotional pull is tougher to come by.

This is true whether it’s a character study, a comedy, a mystery, an action, or a horror.

The story is the character.

I was by no means alone in my misuse of a “character arc.” To this day, it runs rampant in the industry, and it’s why so many screenplays fall flat.

Plot is useful. But it’s the emotion it generates that makes it so. Without it, it is simply data. It is information.

Perhaps the most obvious sign that the writer has forgotten this is a character transformation that feels tacked on to the plot. It sits atop the narrative rather than integrated with it.

If you rely on it for emotional resonance, you will fall short.

ARGO is a prime example of a less-than-meaningful “character arc.”

I love the movie. It works because it does the steadfast character, changing those around them so well. For some reason, however, the filmmakers didn’t have enough faith in that.

Affleck’s Mendez character has a core belief and rallies the CIA, Hollywood, and the hostages to believe in him, the plan, and themselves.

Yet, at the end, they try to give Mendez an “arc.”

Apparently, he hasn’t paid enough attention to his family, and now he’s learned his lesson and comes back, thus the line, “Can I come in?”

But this has not been a story about Mendez’s need to grow to solve his dilemma.

Until this moment, this is a story of triumph against all odds through determination as he transforms everyone around him to get this impossible job done.

The “growth” they give him was never really part of the movie.

It is a result of the journey, so it feels like an additional piece rather than the conclusion.

As a result, it lacks the emotional pull you would expect from this moment.

I suspect that if this reunion with his family had been treated as one of triumph, it would have hit us harder.

Mendez deserved that. The audience deserved that.

We should have experienced the moment of pure existential joy when Mendez sees his family again. And his wife’s relief that he came home at all. That lovely moment with his son would have played better, too.

Instead, we got contrition.

All for the sake of an arc we didn’t want, and we didn’t need.

I love this film, and it’s not intended as a smarty-pants gotcha (fourteen years later!) but something to think about for our own screenwriting.

If ARGO hadn’t done everything else so well, this ending would have been a complete letdown as an emotional resolution to the journey.

You must know why this journey and why this character.

SOUTH PARK had an episode nearly 20 years ago that mocked the randomness of FAMILY GUY jokes. In essence, the FAMILY GUY “writer’s room” was two manatees swimming in a water tank that picked out random words and put them in a “joke combine.”

The result was a joke, like “Remember that time I had dinner in Mexico with Gary Coleman.”

It was merciless, but not too far off.

A lot of us do that for our stories.

Don’t let the narrative and the transformation feel randomly put together.

Even more common, as in the ARGO example, the change is an outcome of what transpires rather than instrumental to the conclusion.

The audience feels the disconnect.

Now, they may look past it. They may not care. But they don’t feel it in their bones either, and this leaves you zero room for error anywhere else.

Build it into the narrative's DNA.

This starts early. We talk a lot about starting points in the Story and Plot Pro community.

Rarely does an idea come to us fully fleshed out. It’s great when it does! But it’s a rarity.

Usually, we start with a character, a world, a dilemma, or a movie cousin. It starts as one part of the whole.

It’s up to us to find the rest, and we can’t keep manatees in our basement for this. We need to figure it out for ourselves.

If we start with a world, what character would be uniquely affected by that world? Pay close attention to the word "uniquely." We want specifics. Generalities fall short.

In CODA, a daughter wants to chase her own dreams, even though she is the only hearing child of deaf adults. What is her dream? Music. Specifically, singing.

In ALIENS, Ripley (still reeling at the death of her own daughter, a fact strangely trimmed from the theatrical version) develops a motherly affection for Newt and must save her from another mother, the Alien queen.

If we start with a character, what world or situation is uniquely positioned to challenge him?

In GRAN TORINO, a Korean War veteran resents how his neighborhood has changed. Estranged from his family, he wants nothing to do with anyone but ends up reluctantly mentoring a young Asian kid who tries to steal his car!

Look to the WHY.

I remember reading an interview with screenwriter Michael Goldenberg back in 1997 that has always stuck with me.

They had a draft of CONTACT that was reasonably good but not good enough.

Neither Zemeckis nor Jodie Foster was fully ready to commit. Something was missing from the screenplay.

Until Goldenberg asked, “Why?” What was behind the main character’s driving want?

And he came up with the answer of her loss and need for deeper meaning after her father’s death when she was a child.

Suddenly, the first act opened up, as did the answers in the third act, and it became the emotional anchor of the movie!

Connect all three acts.

This is one singular story, and it’s not just the plot that connects the acts. To maximize the payoff, that plot has a purpose, and that purpose is to force the choices that push the character’s journey.

Act 1 is who they are before the change.

Act 2 is what changes them.

Act 3 is when the change is tested. They either pass or fail that test.

This is why the midpoint is so important as a pivot to the character, not just the plot, and why I usually break that journey down into at least four primary throughlines.

That final test is key.

It is the final choice that signifies the transformation. And it is directly or metaphorically connected to the character's identity in Act 1.

If the character LEAPS there rather than fighting through Act 2, the choice seems to just “appear.” It doesn’t feel earned, and it will not affect us.

The only thing that’s important is the emotional reaction.

The proof is in the pudding.

If you can get away without a real character transformation, there is nothing wrong with that.

Sure, AIRPLANE and ANCHORMAN feigned those narratives, but did anyone really care? Nope! It helped us to lean on something, but no one pretends it matters. We were having a blast regardless.

Sometimes, we just want to turn it up to 11 and jam.

You have to be really on your game to pull that off, and it’s a tall order to do so consistently.

Even James Bond ran out of steam, and no one did it better! It makes me feel sad for the rest.

I thought JURASSIC PARK: REBIRTH did a fine job with a transformation after the fact. We were there for the dinosaurs, after all.

We wanted a good monster movie, and that’s what we got. It's shallow, but it's fun. But you think that’s easy? The three previous installments would suggest it’s not.

So, yes, you can do it. Others have pulled it off.

But, surprisingly, it’s the harder way to do it.

Along with what makes me care more about the story, I worry about what makes my job easier.

How do I maximize the emotion of this story without forcing myself to hit it out of the park in every moment of every scene?

The only reason I am ever willing to make my job more difficult is because the emotional payoff is stronger.

If the payoff is the same, I go for the easier, higher-percentage shot.

That might sound like a strange reliance on analytics for an art form, but believe me, that assessment is as intangible as it gets.

From an audience perspective, there are no extra points for difficulty.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

Tom Vaughan

Tom VaughanWhen you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline