Sequence 4 and how to attack it.

The pivot into Sequence 4 is not an independent choice. It is dictated by the needs of the larger choices around it.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

Act 2 is often where screenplays go to die, usually out of boredom.

I've had two major breakthroughs in understanding how to write Act 2.

The first was before I sold my first screenplay, and that was realizing the importance of the midpoint.

It rocked my world and changed all my Act 2s after that. It was the single most significant change I made with that script that I sold.

Later, as a professional, my lack of consistency and any real process was driving me crazy until I eventually figured out how to divide the acts even further into what would eventually be 8 sequences.

A sequence that can sometimes create a lot of havoc for the writer is Sequence 4, what I call "First Attempts."

This sequence, predictably, comes right after Sequence 3, "First Steps," and right before the midpoint.

The biggest hint of how to implement Sequences 3 and 4 comes from their seemingly similar-sounding names:

First Steps refers to the protagonist's first steps into the strange, new, special world. They are explorers here. Sometimes emotionally, sometimes literally. Often both.

In Mastering Structure, I define Sequence 4 - First Attempts as:

The protagonist finds more focus and begins their first legitimate attempt to solve the problem.

The pivot into Sequence 4 is not an independent choice. It is dictated by the needs of the larger choices around it.

If I embrace the midpoint as a false victory or a false defeat, then something has to lead to that outcome. Something drives the story to that moment.

That is the job of First Attempts.

The protagonist switches from reacting to their new environment to a specific goal that they think will solve their problem.

The midpoint is the result of this attempt.

It is about narrative momentum.

And the lack of dramatic momentum in 2A is where even good writers can get bogged down.

They can craft elegant sentences, create engaging scenes, and write truthful dialogue. There is nothing actually wrong with any one page.

But as the dramatic momentum slows, so does the level of engagement. This is often because they treat ALL of 2A as one long Sequence 3.

The narrative waits for the midpoint to happen rather than action driving us there.

I like Blake Snyder's term for Act 2A, "Fun and Games."

He describes this act as the place where the promise of the premise is fulfilled.

That is accurate and wisely noted.

But this doesn't help us with dramatic momentum.

Do not meander through this act.

A protagonist reacting to their new environment isn't the worst thing for Sequence 3, but by Sequence 4, someone, either the protagonist or the antagonist, must drive the action.

They do this by a clear want that pushes us through the scenes.

Think of a larger pipe going into a smaller pipe.

Sequence 3 is more general, farther away from an outcome. That is the larger pipe. It narrows as it rushes into Sequence 4.

The protagonist gets more specific in their want. They have a better idea of what they have to do to solve their problem.

As water rushes from a larger pipe into a narrower pipe, the velocity of the water increases. So does the narrative momentum.

Know where you are going.

The best thing you can do for your Act 2A is to know what your midpoint is.

As soon as you've made that choice, you have narrowed down your options of what Sequence 4 is going to look like because there are only so many ways to get you there.

In my spec script MOST WANTED, the protagonist is trying to find the antagonist, his old high school bully, and bring him to justice.

I knew the midpoint would be a confrontation between the two of them, where the antagonist would absolutely demolish our hero.

So, at the end of Act 1, he decides to hunt him down, and at the midpoint, he finds him and gets his butt kicked.

The pivot into Sequence 4 is the point in the middle. So I make it his first legitimate clue to find the antagonist's location. That's it.

Following that clue is Sequence 4.

The key here is the scenes.

How do I make obtaining that clue fun? How do I make following that clue fun? How do I make the confrontation fun?

But the narrative itself? Pretty simple. He gets a clue. He follows it.

In doing so, we create a generous framework for what is really important: great characters in great scenes.

Some movie examples.

LEGALLY BLONDE

A favorite example of Blake Snyder's, Elle is a fish out of water at Harvard Law School. At the end of Act 1, Elle gets accepted to the school. The midpoint is when she is chosen to help a professor with an actual trial.

The pivot to Sequence 4 is when she realizes she will never be accepted by the others and commits to doing well in law school, thus eventually earning the midpoint.

STAR WARS

At the end of Act 1, Luke agrees to go with Obi-Wan to deliver R2-D2 to Alderaan. The midpoint is when they arrive, Alderaan is gone, and they are trapped by the Death Star.

The pivot to Sequence 4 is when they leave Tatooine. They have escaped the Empire and are on their way to Alderaan to solve their problem.

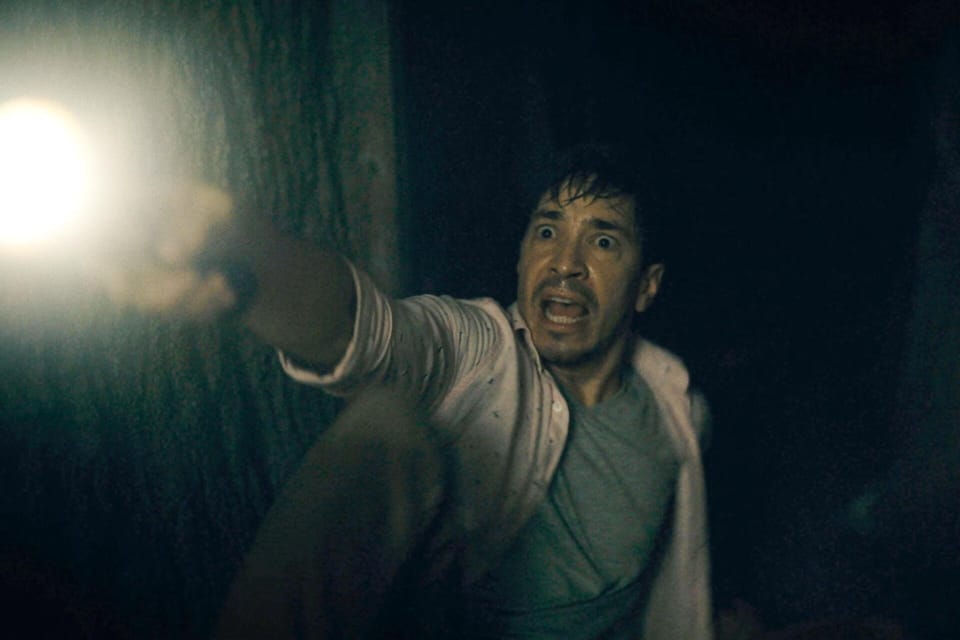

WORLD WAR Z

I love WORLD WAR Z's structure as a teaching tool. Its sequences are simple and clearly defined by drastic events or a shift in location (all the more amazing considering its troubled production).

At the end of Act 1, Gerry agrees to help find a way to fight the zombie epidemic. The midpoint is when the onslaught of zombies overtakes the walls of the last standing city, Jerusalem.

The pivot to Sequence 4 occurs when they leave Korea and head towards Israel, where they believe they will find the answers to solve their problem.

Where you think you're stuck isn't always where you're stuck.

If Act 2A is freezing you up, it's likely because you have not yet made the choices that will clarify what it needs to be. These choices include:

- The end of Act 1 and the dramatic question it creates.

- The protagonist's want. What do they think have to do to solve their problem?

- Your midpoint.

- The story itself and how the character's "old ways" are insufficient here.

This is what I mean by structure as a crossword puzzle, where each choice makes every subsequent choice easier.

Make the big choices first.

Let the smaller choices come to you.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline