Screenplay structure is fractal.

I approach each screenplay structure as a fractal and have found that the most satisfying screen stories follow this pattern.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

I approach each screenplay structure as a fractal and have found that the most satisfying screen stories follow this pattern.

What do I mean by fractal?

- Beats make up the structure of scenes.

- Scenes make up the structure of sequences.

- Sequences make up the structure of acts.

- Acts make up the structure of the story.

Generally, the patterns are consistent and repeat, with elements measuring roughly equal amounts of time.

For example, 4 acts will be roughly 25% of the story each.

Of course, there are plenty of exceptions, and "roughly" is doing a lot of work here, but you get the idea.

There is something to the rhythm of a story, once established, that pays huge emotional dividends when it is adhered to.

This is why the midpoint elements always seem to come around the actual midpoint, dividing the story into two equal parts.

Not to mention, what would we even call it if it didn't?

Breaking a story into equal parts just seems to make it much easier to outline and so much easier to maintain dramatic momentum and emotional resonance.

There is a balance and musicality to the journey that is satisfying.

I suspect this has something to do with taking in the experience in one sitting, as opposed to a novel, which can be absorbed at the rate the reader chooses.

The novel is rhythmic in the sentences, paragraphs, and the chapter, but not necessarily as a whole.

This is why writing with no idea where you're going can sometimes work in novels, but ends up a laborious brainstorm with screenplays.

If that is your process, fine, but there is no way around that it is a more difficult and time-consuming way to wind up in the same spot.

Recognize the whole by respecting each part.

Early on, it's easy to get excited about pages. It's the volume we produce that gets us excited.

This is natural and part of building confidence, and few things are more important than confidence in screenwriting.

So, yes, celebrate a day of pages. That feeling of accomplishment is real; we need as many "atta boys" as possible. However...

The quality of the work is more important. And that quality can be defined by knowing the job of each element and how well you achieved it.

To nail the story, you must nail the acts.

To nail the acts, you must nail the sequences.

To nail the sequences, you must nail the scenes.

And to nail the scenes, you must nail the moments.

Do not rush past anything.

This is the single greatest error we make in our early writing.

We rush through the scenes.

We get so excited about producing pages that we zoom through a scene just to get to the next.

We think we are telling a story because we are getting all the information of the story out. "This happens, then this happens. Then this happens."

But the whole is only as strong as its parts.

And a scene that exists solely to get to the next scene tends to fall flat and slow everything down.

A scene has a job.

And that job is to have an event or an emotion that creates the next scene while still being compelling in its own right.

Get the Now right.

"You better get comfortable with the present moment because the present moment is all you are ever going to get." — Eckhart Tolle

As much as we talk about great scenes and sequences, it's important to understand that total control of each present moment allows those great scenes and sequences to happen.

The moments create the emotion that creates the great scenes.

Like every scene creates the next scene, every moment creates the next moment. Each is affected by the previous moment and then affects the next.

Cause and effect.

You write the scene like you write the sequence.

If you have taken my free course Screenwriting for Beginners, you know the broad strokes of how I outline: I identify the last scene of each sequence, and then I look to connect them.

First thing is to know the story I want to tell.

For example, "This is a story of a man foolishly unhappy with his life, who chases down his high school bully thinking that's where his life went wrong, only to realize how grateful he is for everything he already has."

So now, the big question is, how do I get from "foolishly unhappy with his life" to "grateful for everything he has" via "chasing his high school bully."

What sequences need to happen to connect the story's first scene with the last?

I answer this question by identifying the last scene in each sequence.

For example:

- The inciting incident is the last scene of Sequence 1.

- The Act 1 break is the last scene of Sequence 2.

- A pivot scene when the protagonist gets more specific about what they need to do ends Sequence 3.

- The midpoint is the last scene of Sequence 4.

- And so on...

If I know the last scene in each sequence, the narrative path is already set. My job now is to connect them.

What scenes need to happen to connect the last scene of one sequence to the last scene of the next?

Each of these scenes will contribute in at least one of two ways:

- To get us there truthfully.

- To get us there in a compelling way.

Let's say, for our story, the inciting incident is that the protagonist learns his high school bully is a wanted fugitive.

My job is to choose what needs to occur in Sequence 1 before that happens.

Then, at the end of Act 1, our hero decides to drop everything in his life and hunt down his bully. Great!

My job, then, is to get the audience to believe he actually makes that choice! What needs to occur so they buy the emotional truth of that decision?

That's easier said than done, and why we get paid the big bucks.

So then, let's say I decide the end of Sequence 3 is when he finds his first big clue inside a submerged car.

My job?

How do I develop six or seven compelling scenes that get us from him deciding to hunt down his bully and finding that car?

And so on...

Identify the scenes.

I do this by determining what needs to happen in each scene that affects the next and gets us closer to the end of the sequence.

Or, as I prefer to ask, "What changes in the scene that moves the story forward?"

What is true at the end of the scene that was not true in the beginning?

If I know what change needs to happen in the scene, I can now ask,

What moments need to happen to bring about that change?

How do the moments inside the scene collectively lead to it?

With each moment contributing in at least one of two ways:

- To help make this change happen truthfully.

- To help make this change happen in a compelling way.

Look familiar?

Do you see what I mean by fractal?

The moments make up the scenes, which make up the sequences, which make up the acts.

Each with a job to contribute to the whole, which is to tell the story.

Oh, and make it organic and emotional, too.

Easy, right?

The 30,000-foot view of structure changes your writing.

It happens to all of us. We see the whole structure in one view for the first time, whether we put it on a piece of paper or up on the corkboard.

We see it. Beginning to end. It's beautiful.

But most of all, it makes the endeavor seem so… doable.

But the downside is that we see TOO much of the big picture. We have acts, turning points, and everything the books teach us.

But we forget the scenes. Sure, we get the plot in there. Events happen, and then the next scene comes around.

However, the greatest asset of seeing the whole is knowing the why of the parts.

Because if you know the minimum a story element needs to do to complete its job for the whole, it allows you to focus and isolate that part to improve it.

Each part becomes its own story.

And now you get to have fun with finding the most compelling way to tell that story.

A video recommendation.

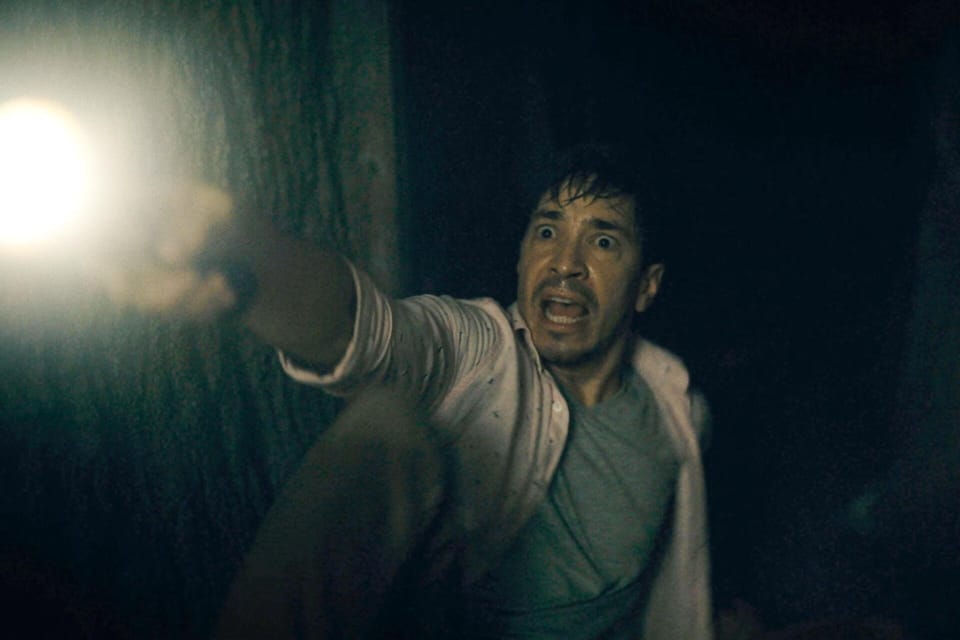

Friend of The Weekly Email Jonathan Stokes has a new season of his YouTube series, Raising The Stakes.

They are an absolute must-watch if you're interested in screenwriting. I am not exaggerating when I say I learn something new with each one.

Jonathan is an accomplished screenwriter in his own right and a natural teacher. If I get my way, I want to see him teaching more.

Speaking of music and rhythm, here is his latest on dialogue.

Click here to watch Raising The Stakes.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline