Scene work: One moment generates the next.

The best screenwriting class I ever took was Jose Quintero’s acting class at the University of Houston.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

The best screenwriting class I ever took was Jose Quintero’s acting class at the University of Houston.

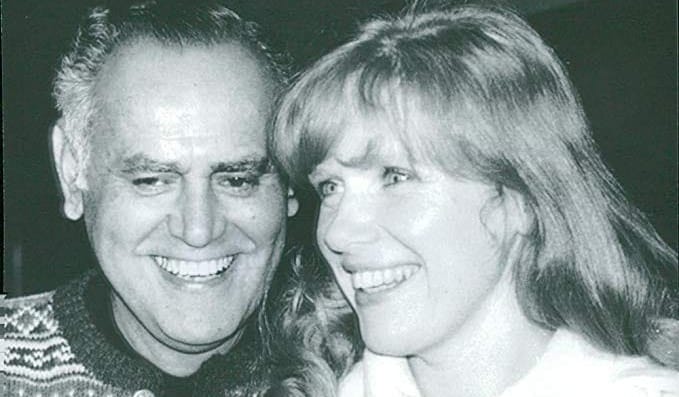

Quintero was a titan of American Theatre. A Tony-winning director, largely credited with bringing Eugene O’Neill back to Broadway, he was also co-founder of the Circle in the Square Theatre.

He would teach every fall at UH.

This is in addition to the spring, when I had Edward Albee teaching me playwriting.

We were all too young to fully understand how fortunate we were.

In an added bit of trivia, this was also the start for my schoolmate Jim Parsons, who later had monumental success in The Big Bang Theory on television. Jim was in the last play I wrote at UH, where I tried to give him all the great lines because he was just so damn good.

Now, Jose Quintero was not as famous as Edward, but he was a truly gifted teacher.

It wasn’t until 20 years later that I realized just how much he influenced everything I do.

As an example, I worked on a scene in class from the play A Hatful of Rain with my friend Amy.

This was traditional scene work in an acting class. Amy and I rehearsed the scene together and performed it for the class.

It was fine. Amy was (and is) a talented actor, and I could phone it in with the best of them. The scene was perfectly acceptable.

But then Jose would work it with us.

Part director, mostly teacher, he would show us moments we missed.

And more importantly, how that moment would create a reaction, and how that reaction would create a new moment, and there would be a reaction to that moment.

And now suddenly, that scene, with the exact same text, was ALIVE.

It was the listening and the reacting truthfully that made the scene. Each moment was a reaction to the previous moment.

To change any single moment would be to change the direction of the scene.

One moment begets the next moment.

Which begets the next moment.

Which begets the next.

The law of inertia and life.

A body at rest stays at rest. A body in motion stays in motion until acted upon by another force.

This is true about the emotion of the moment and the driving action of the scene.

- The emotion of a moment will continue until something changes it.

- A character will pursue what they want until they get it, or something forces them to change.

Think of the great line from Sanford Meisner:

“Don’t do anything until something makes you do it.”

It is the causation of each moment that gives the scene life.

It creates emotion, introduces unpredictability, and conceals the writer's puppet strings.

It also creates momentum.

As one moment affects the next, it carries the audience’s attention along with it, compelling us to keep watching.

When moments lack causation, the audience tends to resist.

Something doesn’t quite feel right. The flow is halted. We get confused, and we reread, trying to understand what happened and why.

It’s one of the quickest ways to yank the audience (the reader) out of the scene.

Do not let a scene exist just to get to the next.

If a scene has more than one moment (as opposed to an establishing shot), it should include both action and reaction.

Yes, the scene exists for a reason. Something must happen; something must change. But we want to avoid jumping from A to E if A cannot truthfully lead us to E.

Either create the emotional journey of A→B→C→D→E, or start at D and then go to E.

The trick, of course, is how to make these moments interesting, fun, or compelling to watch in their own right.

We may need the logic of how to get from one moment to the next, but the logic is not why we are here.

We are here for the emotion.

Learn to read from someone else’s POV.

The flow that you think is in the scene may not be there for the reader. This is a major learning curve for most early writers.

The cause and effect within a scene may be very clear to you, yet the reader bumps. You see it; they don’t.

Clarity of intent is a learned skill. Learn to be very clear about what a reader sees, what they understand, and what they think is going on.

One moment and then the next.

Here is an excerpt from the first draft of a student script.

Now, this is fine. An uptight father discovers his daughter is into risqué dance. But something doesn’t quite flow, does it?

Even though it’s just a matter of physical direction, the lack of lineage from one step to the next makes it somewhat difficult to read and visualize.

When you break it down, you can see why:

- The officer’s words make Sheriff John turn around.

- The sheriff moves in for a closer look.

- The officer comments that it looks like Janet.

- We get a close look. It is Janet.

- Sheriff John reacts.

- Realizing he needs to cover up his own reaction, he pushes back on the officer, “You think you’re funny?” and ends all further discussion by claiming that is not his daughter and walks away.

Notice how many of these steps are independent of the moment before it. This is why the action kind of flickers, moving in fits and starts.

- The sheriff moves closer to the poster before fully realizing why he should.

- With the sheriff already there, the officer isn’t as motivated to say, “She looks like Janet.”

- The sheriff’s turn to the poster is interrupted by the officer’s dialogue.

- The sheriff asks, “You think you’re funny?” but we don’t get a reaction.

- The sheriff adds two more lines with only his own internal discomfort motivating him.

Again, this is okay. It’s just not optimized.

But if we do a quick pass and PUT the lineage in, suddenly it’s an easy read.

What’s the difference? In the rewrite:

- The officer’s words make Sheriff John turn around.

- Realizing that the sheriff doesn’t know what he means, the officer clarifies, points, and says, “She looks like Janet.”

- This makes the sheriff come closer to the poster himself.

- Now that he has moved closer, he sees his daughter in the outfit.

- He reacts.

- Realizing he needs to cover up his own reaction, he pushes back on the officer, “You think you’re funny?”

- This forces a reaction from the officer, “Sheriff?”

- Since he was apparently unclear, John intensifies, “You think my daughter would degrade herself like that?”

- Realizing he just insulted the sheriff, the officer states plainly, “No, sir.”

- The sheriff ends all further discussion by claiming that it is not his daughter and walks away.

Here, each moment is generated by the moment before it.

Now, we don’t need to add the extra dialogue exchange between the sheriff and his officer, but the back-and-forth accelerates momentum and emotion.

If you needed space, that could be cut, but now it is the officer’s reaction that motivates the sheriff’s lines rather than his own internal discomfort.

This is just a quick scene of quick action.

But this concept goes for the larger structure as well. In an email from last year, I wrote about how screenplay structure is fractal.

→ Stories are made of acts.

→ Acts are made of sequences.

→ Sequences are made of scenes.

→ Scenes are made of beats.

→ Beats are made of moments.

Causation is there for each one.

Just as one moment leads to the next moment, one scene leads to the next scene, one sequence leads to the next sequence, and finally, one act leads to the next act.

This is why we refer to it as momentum. Either emotion or physical action (a dramatic question) pushes the audience’s attention from one step to the next.

Look at your scene work.

Look at the actions and the choices that are made in the scene. Is there a life in the scene beyond you just telling characters what to do?

- Does the scene take one moment at a time?

- What makes a character do something?

- Can you have a character respond to something in an emotionally surprising way that feels truthful?

- How does that force the others in the scene to react?

- What choice do they make?

A movie is 24 frames per second. There is no other way to experience it.

One moment at a time. Cause and effect.

It should be no different on the page.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline