Do we really need to raise the stakes?

Raising the stakes often misses the point. What we really want is for the audience to care more deeply about the story’s outcome.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

It’s a familiar note, “The stakes aren’t high enough!”

This may or may not be true.

Indeed, the stakes are vital. They’re one of the three elements of drama.

- Somebody wants something (objective).

- They’re having trouble getting it (obstacles).

- Something will happen if they fail (stakes).

But often, “raising” the stakes misses the point. It’s another misnomer that doesn’t always accurately describe the problem.

What we really want is for the audience to care more deeply about the story’s outcome.

That doesn’t always mean looking outward for external results.

Physical stakes aren't always the answer.

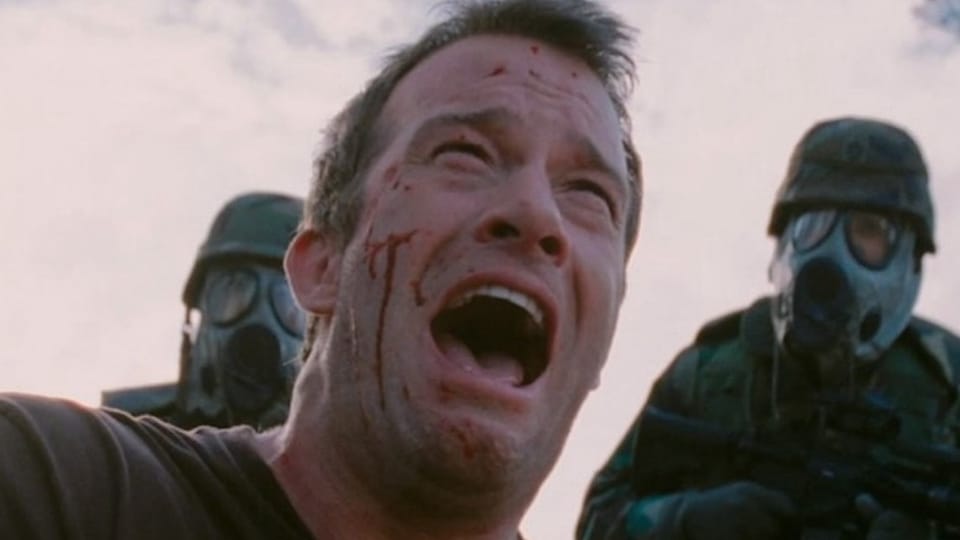

When told to raise the stakes, many writers add more physical consequences to a story.

They put someone in danger or, in some way, increase the violence or the potential of it.

Action films will try to up the number of people in danger as if the threat of five people dying isn’t enough to get our attention, but twelve is!

These kinds of physical stakes can often feel out of place in genres like romantic comedies or character dramas that don't introduce them early on.

If we try to force physical consequences on a story that doesn’t want them, we risk the audience feeling the desperation and losing interest entirely.

Additional subplots can be too much.

I have seen writers add entirely new subplots, like a murder or a terminal illness, just to give the main throughline more weight.

But I have yet to see his tactic work.

Years back, I was hired to write a haunted house movie.

About halfway through development, the company's president wanted to raise the stakes by threatening the nearby town!

This surprised everyone else on the team because people were already dying frequently in the story, and it was unclear if the main characters would survive.

We tried to tackle his wishes, but we never could get that storyline to work. Mainly because it just wasn’t structured for it.

It didn’t raise the stakes as much as it muddied the water.

(It turned out later that he only wanted to do that because a similar tactic worked in his earlier film, which was a huge hit. He was trying to duplicate that magic.)

But stories rarely want MORE.

Going deeper is usually better than going wider.

Look into what you already have.

A better way to generate more empathy and emotional investment is to look at the characters you already have.

Why does the protagonist care?

And how do you get them to care more?

Finding more desperation for the protagonist to achieve their want can go a long way in earning more investment from the audience.

This means asking why they care. We will buy that a character believes the prom is the most important thing in their life if we know why they feel this way.

Are they neglected? Misunderstood? Desperate for validation? For meaning? What does it mean to them to get what they want?

This is why high school humiliation can feel as emotionally grueling as a dramatic thriller because the characters care so damn much.

THE BREAKFAST CLUB, a movie about low-stakes detention, has lasted for generations because the characters are deeply invested in it.

The character’s wants, background, worldview, and expectations of the future matter for their

A romance will feel very different for someone who is unlucky in love than it will for someone who has been married six times.

What does the protagonist fear?

This is another way into a character’s desperation from a different angle.

What do they fear?

And will their failure bring about this fear or prove it true?

BARBIE fears her life will never be perfect again. She has all the flaws and imperfections as… well, us. Yet, we are on board for this whole adventure because this is horrifying to her.

She must fix it. Her life depends on it.

And so suddenly, we care deeply about a woman terrified of having a less-than-perfect life!

None of us care about a pre-pubescent beauty contest, yet LITTLE MISS SUNSHINE is riveting. Nearly every character operates from a place of fear, highlighted and made all the more poignant by the fearless little girl.

Who is your stakes character?

This is not your protagonist. This is who bears the brunt of your protagonist’s failure.

Look at the stakes for that person and the stakes for the relationship.

With stories about positive change, every relationship should be healthier in some way, shape, or form. What we mean by healthier can get complicated, but it should be healthier nonetheless.

But that means failure can also threaten to damage the relationship as well.

In a high physical stakes story, the stakes character can be easy to identify, but who is your stakes character in a smaller, more emotional character piece?

I often reference MANCHESTER BY THE SEA because I love it so much.

In that story, the protagonist, Lee, has already experienced the worst thing that could have happened to him. Nothing is going to be worse than that for him.

But life is for the living, and his nephew needs him. His nephew's future is at stake if Lee can’t figure out how to rejoin the land of the living.

His nephew is the stakes character who bears the brunt of Lee’s decisions.

It makes Lee’s story matter beyond just himself.

What is the alternative?

If the protagonist doesn't get what they want, who does?

Movies with antagonists that we love to hate have such an advantage here. Early in my career, I neglected the antagonist character. I didn’t put enough effort into them, even for my action films.

I don’t make that mistake anymore.

We can get so much mileage from a character the audience is rooting against. Regina George in MEAN GIRLS, Terance Fletcher in WHIPLASH, and Shooter McGavin in HAPPY GILMORE.

We can be as committed to seeing the antagonists lose as we are to seeing the protagonists succeed.

Sometimes, this includes the philosophy the antagonist embodies, like in THE KARATE KID.

We aren’t just rooting for Danny to win; we need Kreese and his whole outlook to be disgraced.

The audience will care more if the character cares more.

Some stories will do just fine by increasing the physical danger.

But that’s not always an option, and even if it were, it’s not always a good one.

If a character isn't scared, we won't be scared.

If it doesn't matter to them, it won't matter to us.

Always look to unpack what you have before trying to bring more to the party.

That's a wrap!

It was another huge week for the box office, with TWISTER pulling in over $80 million. It's not exactly THE AVENGERS, but considering people were writing up eulogies for the theatre experience just a month ago, it's not too bad.

IATSE ratified their deal with the studios as well, so things are looking up!

Maybe we'll see an upturn in TV production soon.

Until next week!

Tom

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline