Movies are about moments.

Processing any combination of basic principles is far more likely to lead you down the right path as well as get you out of trouble.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

A few days ago, I posted this on X:

In screenwriting, it's tempting to describe THINGS on the page. Don't. You want to evoke moments.

You are describing what the audience absorbs, feels, and reacts to in that moment.

Your goal is to create for the reader the same moment the audience will have in the theater.

I had some follow up questions about it and I thought it would fun to expand on something that has grown increasingly important to me in my writing.

How I teach.

Getting better at screenwriting is rarely about learning more. It’s about doing it more. It’s almost always about taking what you already likely know and processing it faster or piecing it together in a different way.

As a teacher, I would much rather repeat the same principles over and over again until they are second nature, than offering up larger swaths of information for its own sake.

Processing any combination of those basic principles is far more likely to lead you down the right path and get you out of trouble.

Two guiding principles here.

So when I say movies are about moments, the two guiding principles for our screenwriting are:

- Our goal to evoke the emotional experience of watching the movie on screen.

- Nothing should take longer to read than it takes to happen on the screen.

The two guidelines will tell us how to approach an action. What’s left is to do what only you can do, and that is make a choice about the moment.

Do not get bogged down in detail.

This is the most common mistake. We focus on trying to describe something and what is just a flash on screen ends up taking 20 seconds to read, implying an importance it doesn’t deserve.

This doesn’t sound like much, but…

- It adds up over pages and eventually weighs a screenplay down.

- The reader realizes the writer does not allocate their attention appropriately. As a result, they end up skipping lines, no longer having faith each line truly needs to be read.

Do not forget the emotion.

It’s also common to target lean lines and paragraphs but forget the emotion of the moment. Events happen, but they are empty.

The moment exists solely to get to the next moment. And that moment only for the moment after that.

We’re moving quickly but we feel nothing, we absorb nothing, and we react to nothing.

That’s not what we want from our movies so it’s not what we want from our screenwriting.

Make a choice about the moment.

This is your primary job. To make a choice. About the story, about the scene, and about the moment.

What do you want the audience to absorb from each moment? What do you want us to feel about it?

Some examples:

I often use is the opening of BRIDESMAIDS where a guy’s house is described as “the ultimate bachelor pad.” That’s it. That tells us what it is and how we feel about it. No need to get into any more detail than that.

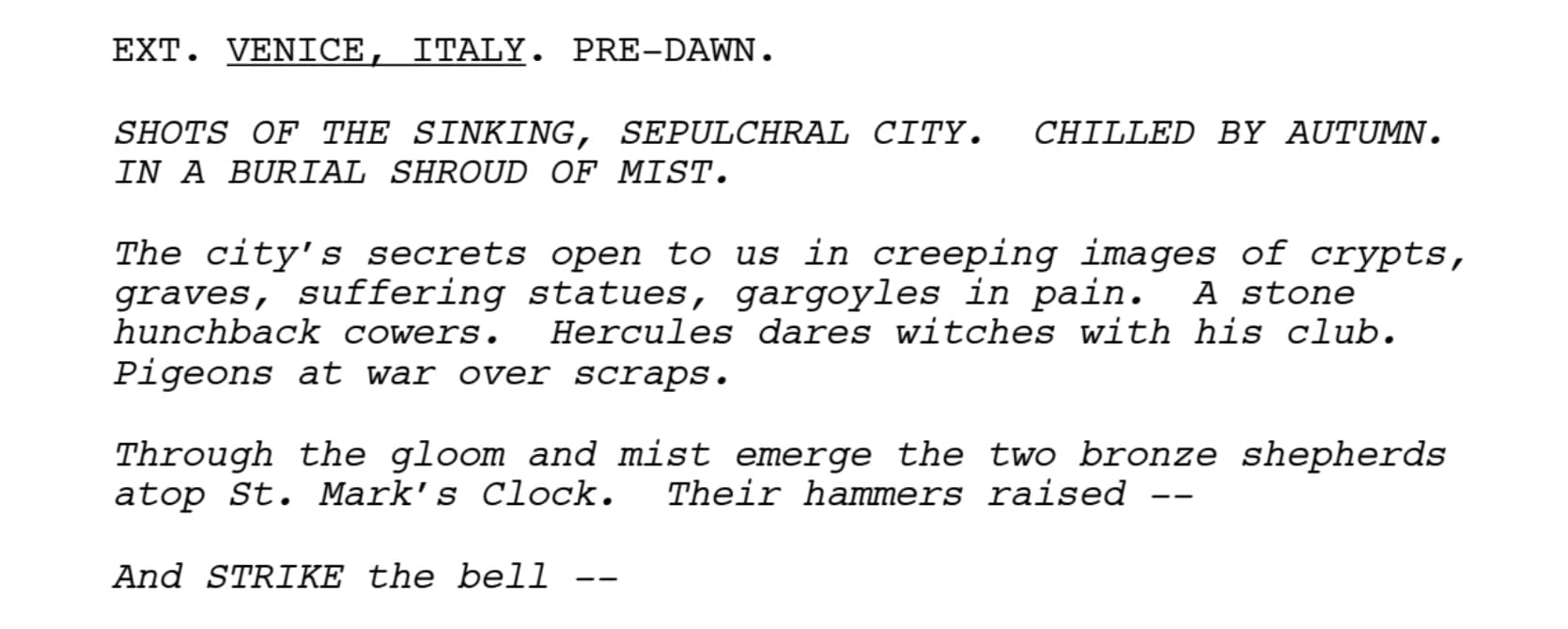

A HAUNTING IN VENICE by Michael Green opens with this.

Not a bad amount of detail, but look closely at the words.

“Chilled… burial shroud… secrets… creeping… suffering… pain… cowers… dares witches… “

Each detail is only there long enough to add to the mood and the feeling of dread.

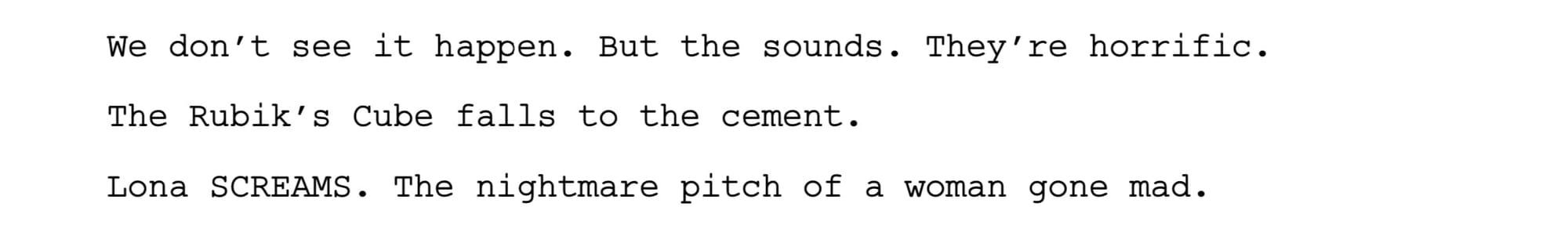

This is from a screenplay of mine called THE GOOD TEACHER. In the opening sequence, a mother watches her child attacked and killed by two dogs. It’s a brutal opening to a horror movie.

The whole scene concludes with this:

I don’t try to describe the sounds. We can imagine. I just say they’re horrific.

I do something similar with Lona’s scream. Trying describe such a thing is a bigger task than I may be up for. So I just focus on the results and hopefully evoke the absolute nightmare of this moment.

I just want the reader to FEEL it.

Describe the action and then what we understand about it.

It is tempting to want to describe how a face reacts. This is a common misinterpretation of “show don’t tell.”

It’s not uncommon to see something like, “Her face clenches and her eyes squint as she takes a deep breath.”

I’m ask the writer, “What does that mean?”

“She’s pissed!”

“Then say that!”

In this sense, “Show then tell” may be more accurate.

“Her face clenches - pissed,” does the job just fine.

Ask yourself what do we see? Then what do we glean from it?

But we need that image first. Then give us the conclusion, and our minds will fill in the rest.

An exercise.

Watch a movie. Something you’ve seen before. Take note of what you take away from each moment.

What information do you perceive? How does it make you feel? How does it lead to the next moment?

What is the moment about?

Pause the movie! Think about it. What did the storytellers just tell you in information, and what did they do to influence how you feel about it?

How do wee feel about a physical space? How do you feel about a character? How do we feel about a relationship? How do we feel about a moment?

That is what you are trying to capture in your screenwriting. The details are only important if they get us there, and any detail that this is unnecessary to do that can be left behind.

Non-choices kill.

I am convinced that making choices about each moment and the clarity of that choices is what separates good writers from those not quite ready.

This is another one of those core principles.

Make choices.

The more you get into the habit of making choices, the better choices you will make.

The goal is for all those choices to multiply each other so the emotional journey is greater than the sum of it parts.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline