It's the intention that matters.

The intention and how well we achieve it are how we measure success.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

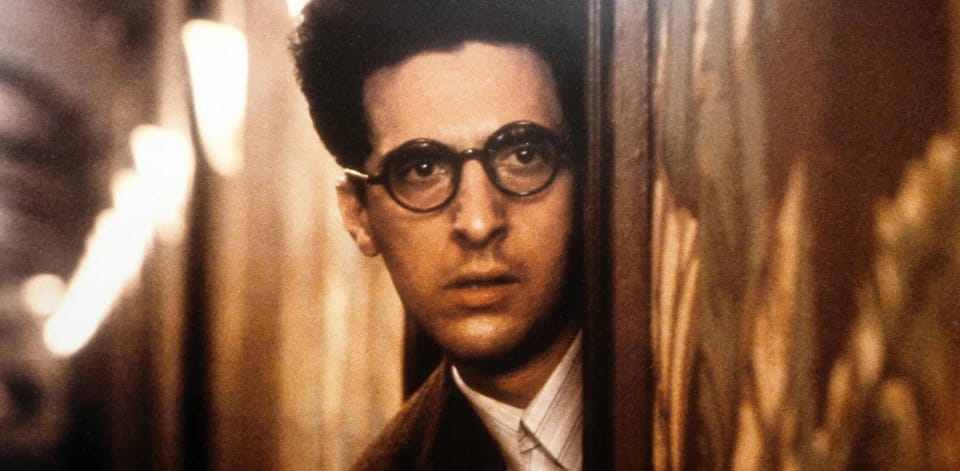

The last play I wrote under Edward Albee's guidance was a drama about a man accused of something awful. The narrative was from his perspective. We (the audience) were rooting for him throughout, and near the end, he was vindicated.

But in the last scene of the play, we discover he was actually guilty of this thing.

Edward wanted to go to black there, and I insisted that the man's son hear this fact. I wanted the play to end with the son knowing his father is a terrible human being.

Now, I could have had a disagreement with Edward about good drama, and he would be right 99/100.

But this time, I thought he was "wrong," and how I wrote it was "right."

The audience responded as I wanted, and I thought this confirmed my choice.

This gave me tremendous confidence. Maybe I actually had some idea of what I was doing! I knew what I wanted out of that moment, and I stuck to my guns, and it worked.

That kind of confidence is crucial for writing.

But I was young and immature, and I didn't fully understand this lesson.

So, later, just a "feeling" of being right was enough for me to dig my heels in. This was true even when I was a writer for hire! Even when I was given an explicit note to "Do this."

And yes, even when I was 100% wrong.

I've written previously about taking notes, both in development and from friends and colleagues.

But I want to cover something else this week.

When to know when we're right and when we're wrong.

What happens when we receive a note and believe it is incorrect?

For starters, right or wrong is often the wrong way to look at it.

All we do is make choices.

That's what screenwriting and storytelling are.

This is why I am not directly threatened by A.I. I have concerns, like anybody, but I am not worried that it will do what I do.

The computer cannot make the same choice that an artist can. It can copy a choice. It can mimic one. It can follow probabilities and programming.

But it cannot actually make a creative choice.

And it's the non-choices that get you.

Every mediocre screenplay is littered with non-choices.

Sure, it feels like choices because words were put down. The sentence makes sense, after all. Aren't those words a choice?

Not necessarily.

A choice has intent.

A lack of intent may keep you out of jail, but if it gets the job done, it does so by accident.

A choice is about knowing what you want to achieve and executing it in a way that achieves that end.

This is true whether it's a story, a sequence, a scene, a moment, or a single word.

Each choice must support the others, reinforcing them and building something greater than the sum of the parts.

For example, you might make a strong choice about a sentence, but if it undermines the choice about the scene, it won't feel like a choice at all.

It will feel like a mistake.

It will feel like a non-choice.

The intent and how well we achieve it are how we measure success.

When I disagreed with Edward on the play's ending, I was young and focused on who was right and who was wrong.

But that was far less relevant than I thought.

It was really about the choice of what we wanted out of that moment.

Did we want to go to black and leave the audience with the realization that they were rooting for the bad guy all along?

Or did we want the audience to focus on the son who now realizes this same thing? This included the moment between him and the dad, with his dad not entirely sure whether the son had overheard what was said!

It's a haunting shift of POV. The protagonist has alienated us. We go from feeling connected to him to complete separation and to now identifying with the son.

Shift away from thinking of right or wrong. It's about being intentional.

Know your intent. Make a choice. And find the best way to achieve it.

For example, if I had followed Edward's advice and decided to go to black, we could have made other choices to make that moment even stronger.

We could have kept the lights down for an excruciating amount of time and let them sit with their realization before curtain call.

That might have been very effective!

Once we made a different choice of what we wanted to achieve, our job then would have been to execute that choice to the best of our abilities.

The intention is all that matters.

Not everyone who gives you notes will realize this. In fact, most will not. They will give you notes that really sound like, "If I wrote this, I would have done it this way."

Or perhaps, "I would like this better."

You would be surprised just how many people will have an off-the-cuff opinion and then behave as if this was a strongly held belief they've had for years!

We don't have that luxury. We are the ones juggling to unify the hundred other choices in the piece.

Now, obviously, if you're in development and you're being paid, it's a whole other challenge, but often it's just you asking someone for notes.

It's up to you to know what your intention is. Does this note help you achieve it more effectively?

Often, however, a note will reveal that you haven't actually made a choice yet at all.

Do not insist you have made a choice when you haven't.

We can really fool ourselves with this. We can feel so close to verbalizing what we mean that we think it's "close enough."

We say, "It's a little bit of this and a little bit of that. Maybe some of this, too."

We can get pretty creative in all the different ways we can say, "I have not made a definitive choice yet."

If you cannot verbalize it, be very cautious about committing to it.

Vagueness is not your friend. Vagueness attempts to hide many things, and none of them good.

The only thing less productive than not making a choice is not realizing you have not made one and then defending that non-choice.

Protect the intention, not the execution.

Once you choose what you want from a moment, scene, or sequence, determine how best to achieve it.

Whenever I hear an idea for a revision, whether it's from the writer, a co-writer, or a third party, the most important question to ask is:

What do we gain by this change?

When we're not operating from a place of confidence, we think in terms of right, wrong, better, or worse.

We're frozen by too many ideas, too many notes, and too many options.

But confidence comes from knowing what we want.

When someone suggests a change, simply ask yourself and them, "What does the story gain by that change?"

And just as important, "What does it lose?"

Does this match up with your intention? Does it execute it better, execute it worse, or change it?

If the discussion is the intent, frame it that way.

In the Albee note, we were debating execution when we should have been discussing intent.

Of course, there is nothing wrong with debating intention, as long as we know that's what we're discussing.

The famous note-behind-the-note is one of three things:

- You did not achieve your intention well enough.

- You don't have an intention.

- A bad note altogether.

If it's either of the first two, the reader doesn't understand how to discuss it in these terms, so they may say, "Do this."

Before you do anything, determine which of the first two is the issue.

#3, unfortunately, is beyond the scope of this email.

One of my favorite scenes started from my non-choice.

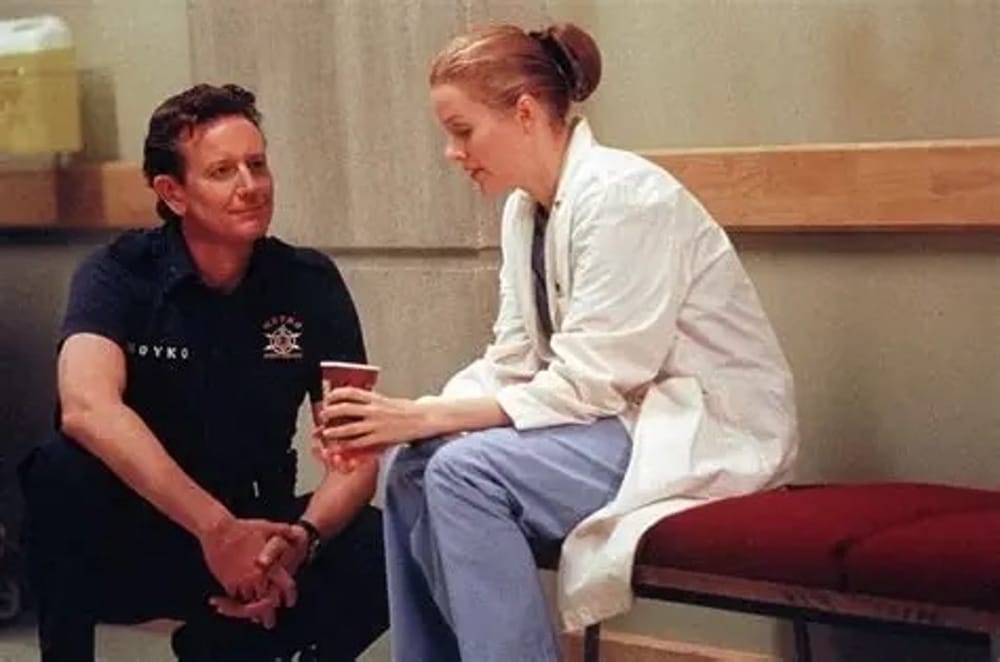

It was a silly TV movie, and we were all just pulling a paycheck. I was hired to rewrite the script, and I spent a lot of time just getting it from horrible to mediocre.

The scene was all exposition with the detective and the doctor interviewing the ex-wife of the killer.

We needed info that would get the narrative to the next scene, and that's how I wrote it. Kind of boring.

The director pushed me on this. He wanted something more. I wrote some cutesy lines. He wasn't satisfied. He kept pushing me.

I was frustrated. I was thinking it was a dumb exposition scene, and let's get in and out.

Much to Dan's (the director's) credit, that was his point. Screen time was too valuable to have a scene that is solely exposition.

The problem is obvious to me now. The whole scene was one big non-choice.

The director knew instinctively there was nothing there and wanted something, anything interesting at all!

But I had no intention to begin with! No means to measure success!

I didn't have the experience or vocabulary to articulate my own problem, let alone a solution, so it came across as frustration.

"What do you want, man?"

Dan didn't have the vocabulary either, but all he wanted was something!

In other words, he just wanted a choice. That's all. He just wanted a choice for what the scene was about.

I eventually played around and found an angle that I liked.

I looked for the emotional layer in the scene and, quite accidentally, found an interesting emotional effect on the ex-wife. That at least gave the scene life.

But the result was an emotional impact on the doctor (one of our protagonists, played by Penelope Ann Miller), giving the scene a purpose beyond the exposition.

It was an experience that would eventually lead her to the humility she lacked.

All I did, after more prompting from the director than should have been necessary, was make a choice.

And it turned into one of my favorite scenes I ever wrote, in a totally mediocre TBS movie.

You can do whatever you like.

What matters is that you know exactly what you want out of it. What are you trying to achieve?

This is true for every word, sentence, moment, scene, sequence, and the entire story.

Have an intention. Once you do, you can measure how well you accomplished it or not.

If your screenplay is one choice after another, with every moment filled with intention, you're ahead of 99% of screenwriters out there.

Pro and non-pro alike.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

Tom Vaughan

Tom VaughanWhen you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline