How I learned screenplay structure.

Plots seem complicated when you're in the moment, but when you lay them out scene by scene it's clear how simple they really are.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When I was 23 years old, I decided I wanted to learn screenwriting.

I was a playwright then with a few local productions, but I really loved the movies. It was clear screenplays were the way to go.

While I had taken a few stabs at it before, I knew I had no idea what I was doing, so I did what I tended to do back then.

I went all in and devoted myself to learning something new.

The time.

This was 1994, and I was living in Texas. There was no internet and no online classes. Only a few books were around, and there was no "screenwriting community."

Screenplays themselves were hard to come by. I owned one script. LETHAL WEAPON 2.

I sent a check for $12 to a shady place off Hollywood Blvd, and six weeks later, they sent me a photocopy of the screenplay they weren't supposed to have to begin with.

To this day, I write gunshots as "BANG! BANG! BANG!" because that's how Jeffrey Boam wrote them in that script.

The plan.

I moved to Austin, and I rented a small room in a house so I could do two things:

- Analyze movies.

- Write movies.

Unfortunately, I was also smoking two packs a day, and my room did not have a window that could open. The air mattress I slept on had a small leak, and I had to blow it up it every night. A friend called my room "the coffin."

It was the kind of life you can only live in your 20s, and with a start-up you believe in. In this case, the start-up was my career.

I went in equipped with this:

- Screenplay by Syd Field.

- Writing Screenplays That Sell by Michael Hauge.

- Lethal Weapon 2 screenplay.

- A friend who owned a video store.

That last one was key. My friend would let me come in 15 minutes before closing, and I could take home any movie they didn't rent out that night.

I retreated into the coffin for six months and only came out to get new movies (perhaps a slight exaggeration.)

Breaking down the structures.

I liked both screenwriting books, but I felt like they were really just pointing me in the right direction. Syd Field's gift was that he convinced me I could learn story structure.

Every night, I would come home with two or three movies. I broke down the structure of the ones I liked or thought I could learn from. This consisted of writing down each scene along with the time code.

I was reverse-engineering my favorite movies.

Unfortunately, outside of some vague ideas of Act 1, Act 2, and Act 3, I didn't have a great idea of what I was looking for. Terms like "Plot Point 1" and "Plot Point 2" left a lot to interpretation.

Here is an example:

Click here for my 30-year-old breakdown of Groundhog Day.

Those marks on the left are me counting the jokes in that scene. I was figuring out how many jokes should be in a comedy!

This was also when I learned that characters could sometimes take drastic turns throughout the story. You can see that on the right.

My preconceived notions about the story structure of my favorite films were often shattered when I broke the structures down.

For a more modern example of this kind of breakdown:

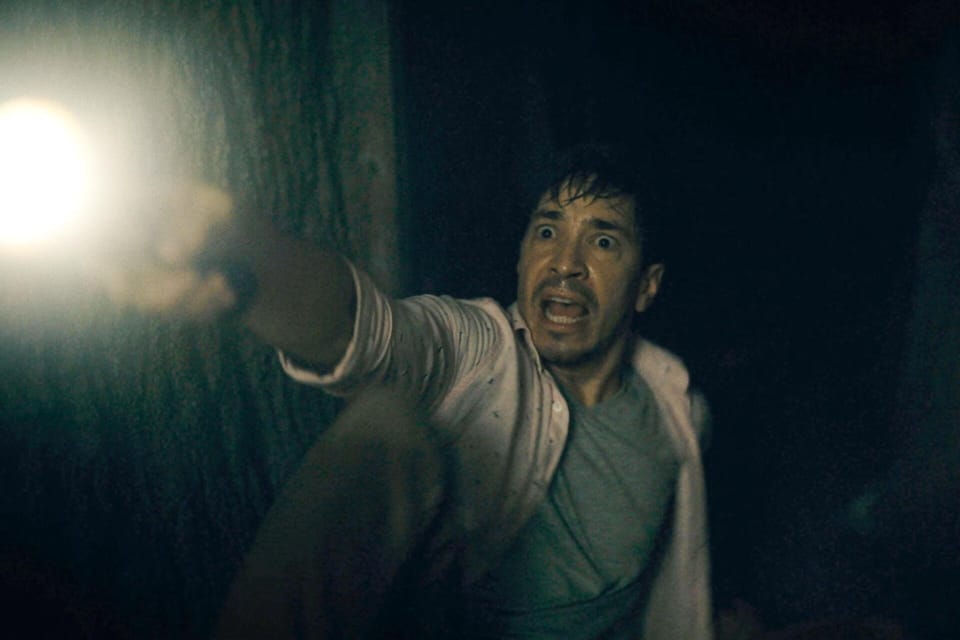

Here is a breakdown of PREY.

The biggest lesson.

Those six months of analyzing film structures built a foundation for me, but the most important thing I learned was just how simple feature films were.

Plots seem complicated when you're in the moment, but when you lay them out scene by scene, it's clear how simple they really are.

Movies are about scenes and sequences, not plot.

Once I realized this, screenwriting became far less intimidating.

I went from, "How am I supposed to think of something this dense and complicated?" to, "I can do this. I just need to focus on great scenes!"

I started to believe I could write screenplays for a living.

My own growth.

I wrote two scripts in this period and sold one of them. Over the next 27 years, I added layer after layer of additional understanding of structure, incorporating more ideas, personal definitions, and a value system of story and emotion first.

In essence, I created a consistent, repeatable process for myself and anyone who wants to learn from me.

You should have had the chance to download my 8-sequence breakdown when you subscribed, but if you didn't, you can do so HERE.

When I teach, these are the building blocks we use to break down story structures. It's fun and full of discovery, but we don't want to lose track of the real goal of all of this.

And that is to help us write our own stories.

The tool belt.

Do not make breaking down a movie an academic exercise. Our job is to expand our own understanding through repetition and to add additional tools to our tool belt.

Struggling with a story point? How did other films with similar structures do it? Struggle with a plot point? What can we learn from the best?

That's the kind of thing we're looking for.

We are not trying to be better movie critics.

We want to elevate the consistency of our own screenplays and learn how to fix what's not working.

The 30,000-foot view.

I use this tool even today for my rewrite process. Here is a breakdown of a recent spec script Kristy Dobkin and I wrote together.

Click here for Another Life.

Our main goal for this draft was to cut. The number on the right is how long the scene or sequence was, and the numbers on the last page told us what acts and scenes were running long and might be a good candidate to trim.

This step is huge for me to get out of the one-page-at-a-time view and see the big picture.

Do it yourself.

If you haven't already, break some movies down. There's no need to be fancy about it; do it on paper.

Write down the time code on the left and the scene on the right.

Identify the inciting incident, the Act 1 break, the midpoint, Act 3, etc… Label these things. Get that 30,000-foot view of the story.

Take special note of the film's sequences. See how long great scenes and sequences take.

You will never regret getting good at identifying another movie's story structure.

There is only upside to getting good at this incredibly helpful skill.

Now, if you DO want to get fancy when you break down a structure, here is a Word doc.

(The A, B, C, and D columns are designed to track the subplots, but that is a more detailed lesson for another time.)

That's a wrap!

I wanted to share an update on some projects this week, but this email is already pretty darn long. Next week, instead!

Want an online version of this email you can share?

Click here.

See you next week!

Tom

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline