Does your screenplay need a promise?

The Promise takes advantage of a simple truth: if we get a taste of something we want, we will likely want it more.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

I have a general guideline within a relationship structure that the audience should see the true potential of the relationship sometime before the midpoint. Maybe during the midpoint at the latest.

The characters don’t have to see it, but we do.

Let’s just call this moment and/or this scene The Promise for right now.

Maybe we can come up with something better later on. (Perhaps someone else already has!)

You will see this moment time and time again in all kinds of love stories, whether they’re romantic dramas, comedies, or buddy movies.

Jack and Rose below the decks before the iceberg hits in TITANIC, for example.

In short, we get a glimpse of what we are rooting for.

This week, I want to discuss a version of this moment in other kinds of stories as well, where the protagonist gets a glimpse of what his or her life might be like after their transformation.

It’s just a glimpse, of course.

They’re not ready for it because they haven’t made the transformation yet.

They cannot maintain this moment.

But it’s there.

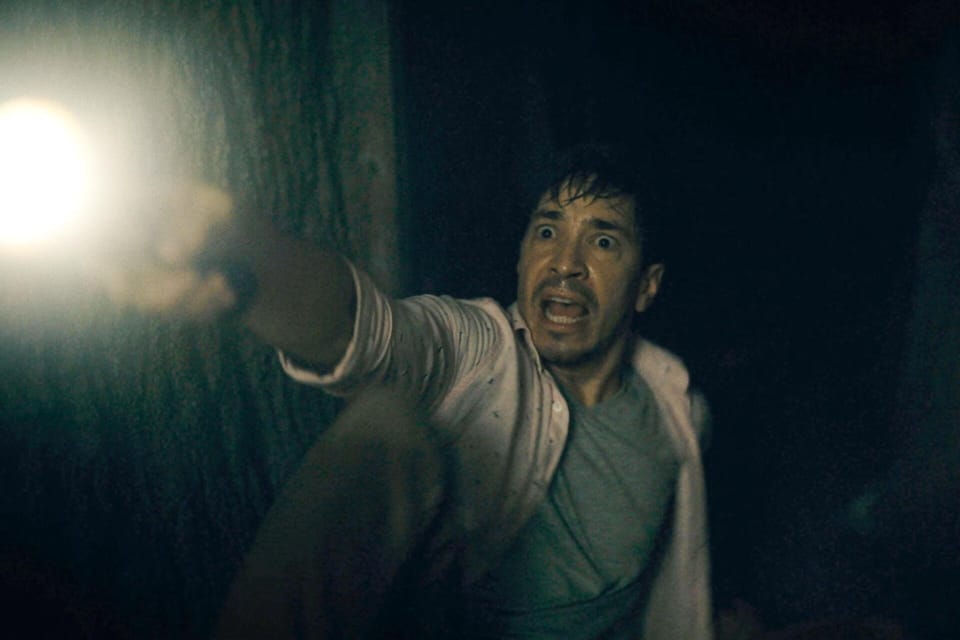

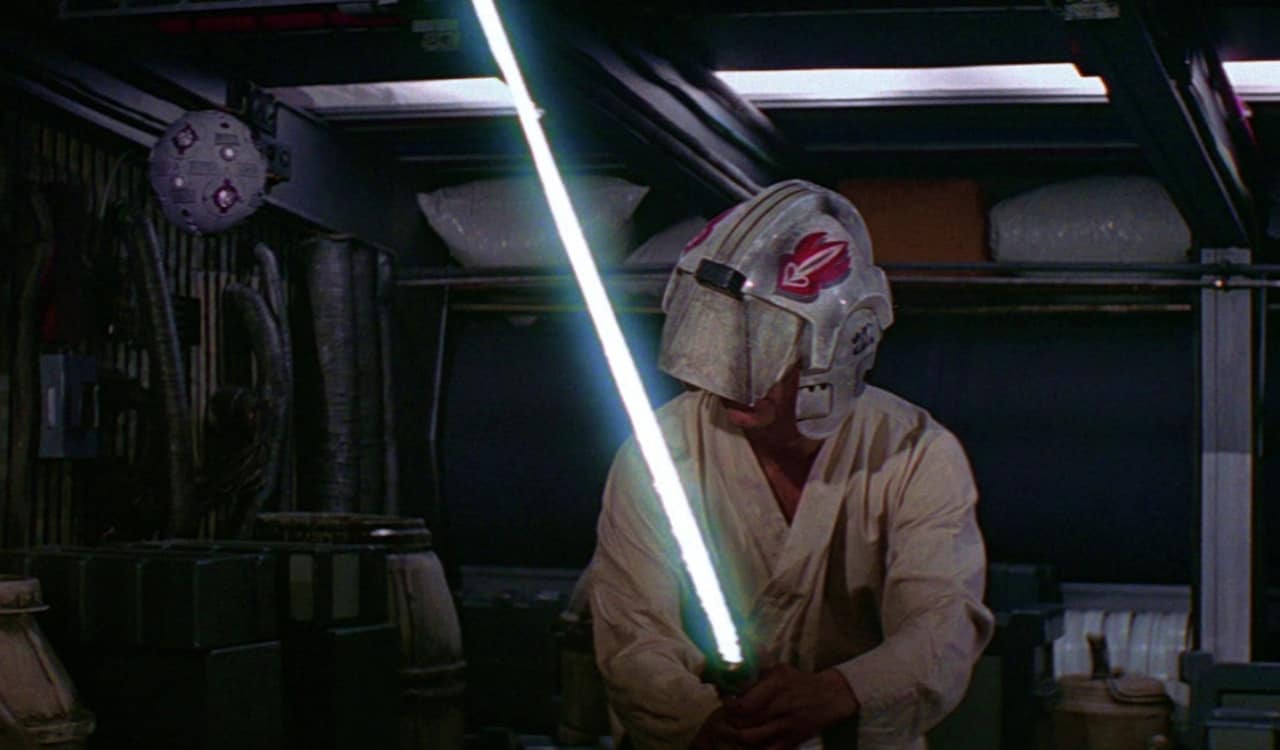

It is a version of the “training” scene we so often see in the hero’s journey, such as where Obi-Wan teaches Luke to anticipate the lasers with his blast shield down on his helmet.

It’s not just “setting up” the choice at the end; it’s offering us a glimpse of what could be.

I don’t believe it is as necessary in other stories as it is in relationship structures, but the emotional potential of this moment can be extremely effective to help engage the audience.

Core ideas revisited.

This simple idea leverages many of the core principles I discuss in the courses and The Weekly Email.

- Transformation.

- The dramatic question.

- Dramatic tension.

- What the audience hopes will happen.

- What the audience fears will happen.

- Emotional reversals.

- Yes/No.

- Victory/Defeat.

So, there is nothing particularly unique about it, other than the placement, and you, the storyteller, recognizing the need for it.

When used well, the scene takes advantage of a simple truth: if we get a taste of something we want, we will likely want it more.

This want, our want, makes us more emotionally invested in the outcome.

In some cases, we can also see what we lose. We give the audience and the characters something, and we take it away.

Know the needs, make a choice.

A big step for a writer’s craft is accepting responsibility for the audience’s entire emotional journey.

From beginning to end.

We are usually pretty good at this on the scene level. We know what we want emotionally from those individual beats.

But an additional level of craft is needed when we account for the entire breadth of the structure.

What is the audience thinking, feeling, and anticipating in each moment?

How do you use these answers to build an emotional journey that is greater than the sum of its parts?

Do not abdicate this responsibility. You are not transcribing events. You are telling a story.

Whatever the audience is thinking, feeling, and anticipating, they are doing so because you have led them there.

So the real question is, what do you WANT the audience to think, feel, and anticipate?

And are you achieving this?

When Luke feels the Force and fights off the practice lasers, we see a glimpse of what could be. We are now rooting for him to continue that journey.

If he were to fail against the lasers and the Force proved useless, we would then be wondering, “Is this old man crazy?”

This is a very different reaction.

Neither is better than the other, depending on what story we want to tell. The point is that a very specific choice is made that generates a very specific emotion.

You, the storyteller, make that choice.

If you want the audience to root for something, it’s your job to make sure they do.

The two purposes of The Promise.

The Promise is usually a glimpse of where the protagonist(s) could be at the end. I can think of two reasons to consciously ensure this moment happens.

It shows the audience what they are hoping for.

We may like the characters and wish them the best, but we don’t always have the opportunity in Act 1 to illustrate to the audience what they actually hope to see at the end.

In many romantic comedies, characters may not even like each other.

In THE PROPOSAL, for example, we don’t really care if Sandra Bullock’s character gets what she wants. Her need to get a green card is an excuse for the adventure.

And there certainly isn’t any romantic chemistry between her and Ryan Reynolds’ character in those early scenes.

We don’t really see how good they are together and how good they would be for each other until later, when they share an honest moment in the bedroom as Bullock is in bed and Reynolds on the floor.

In sports films, you will often see glimpses of the team coming together.

In HOOSIERS, Gene Hackman invites Dennis Hopper’s character “Shooter” to help coach the team, and in the Promise scene, we see Shooter show up for the first time in a suit!

It’s a promising moment, and Hackman tells Shooter that the kids “are starting to get it!”

It’s all going in the right direction.

Soon after, many are asking for Hackman to be fired.

This quick reversal is an added bonus of The Promise, and, as we will discuss in a bit, sometimes its real purpose.

In TOP GUN: MAVERICK, this is where you see the squadron come together as Maverick builds camaraderie by getting them to play football on the beach.

Without their shirts. At the magic hour.

The Promise can also be an empty one, one intended to be yanked away.

This is a failed promise.

In this case, The Promise doesn’t show what could be; it shows you what could have been.

(In the series The Walking Dead, I would laugh whenever a supporting character would have a humanizing moment on the show.

I knew they were most certainly dead by the end of the episode!)

My UH class is watching ALIEN this week.

Many of them have already seen it, but it’s such a delight to introduce it to the ones who haven’t.

We all remember the chest-burster scene, one of the most famous scenes in film.

But think about what happens before that moment.

The crew is together for the last time. Laughing. Full of life.

Sure, Ash looks a little sketchy, but he’s a weird guy anyway.

We get a glimpse of how it could have been. How it should have been.

Not only does this make the moment more grueling, but it also deepens the end of the film when she says, “This is Ripley. Last survivor of the Nostromo, signing off.”

The Promise is not a requirement.

Even in a romantic comedy, you can show us what we’re rooting for at some other time.

It just happens to fit particularly well there.

And plenty of films don’t have this moment at all. In The Avengers, the bickering team of superheroes has an opportunity to show us what could be, but none of them take it.

They are at each other’s throats all the way to the attack on the heliocarrier.

It’s there when you need it.

As with everything, this is a tool for a particular need at a particular time.

What emotion do you want to generate from it?

How does it combine with the emotion before it and the emotion after it to add up to something even more?

Do you need something here to help with the audience’s emotional investment?

Do you want to nudge a character in a certain direction or make them think twice about what they want?

Your job is to know your intention and make a choice.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline