After the midpoint.

The midpoint doesn't change the character. It just changes their direction.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

I spend a lot of time talking about the midpoint.

It was a huge breakthrough for me. It was a significant step in my growth when I discovered its importance to narrative momentum, so I pushed it hard in my classes.

But the midpoint's value isn't an isolated step.

It brings more than just dramatic momentum. It has a vital role in the story as well.

Its value is in how it affects the protagonist, especially in the moments after in the 5th Sequence.

I call it "The Vise Tightens," but only because "Bad Guys Close In" was taken.

While we may use it differently, I have yet to find a better term for it than what Blake Snyder coined.

The midpoint is a shift.

A good midpoint usually works best when it feels like a victory or a defeat. The protagonist either gets what they want and is unprepared for the consequences, or they feel a stinging loss.

It is often the last moment that the character we met in Act 1 remains intact. It is their last gasp as they way they usually solve problems isn't going to work anymore.

But keep this in mind: the midpoint doesn't change the character. It just changes their direction.

It's where their change begins.

And the 5th sequence is where that change happens.

So, if the protagonist is the one who transforms, think of them as an airplane. The midpoint is when the nose turns down.

In the 5th sequence, the wings and stabilizers fall off, and the rest of the plane breaks apart.

Okay, in retrospect, that might be too extreme. But you get the idea.

It's not just plot.

The biggest mistake people make here is that they add more plot without thinking about the emotional effects it has on the character.

They take the "Bad Guys Close In" expression too literally, and only the bad guys close in.

But remember, we don't just want dramatic momentum from our structure; we want emotional resonance as well.

We want to attack the protagonists on all fronts here.

For the characters that transform, we want to increase the pressure on them so much that it kills off the old version of them. For characters that remain steadfast, we want to genuinely challenge their faith in their core belief.

So don't just hit them in terms of plot. Hit them where it hurts.

Find the tensions.

As always, we have to know what story we're telling. If we do, we can ask the all-important question, "What needs to happen?" to transform this character.

How do we get them from A to B?

I have a simple task I do for Sequence 5.

I list out every tension in the story.

That means every relationship, every subplot, and every want the protagonist has.

And then I figure out some way to make it worse.

BRIDESMAIDS seems to go down the list of home, work, and play and destroys them all for the protagonist, Annie. It's textbook. Yet, every scene is fun and heartbreaking and feels fresh.

In BARBIE, Barbie can’t handle Ken's changes in Barbieland. If that is not enough, Gloria and Sasha head back home to the real world as corporate Mattel comes to Barbieland.

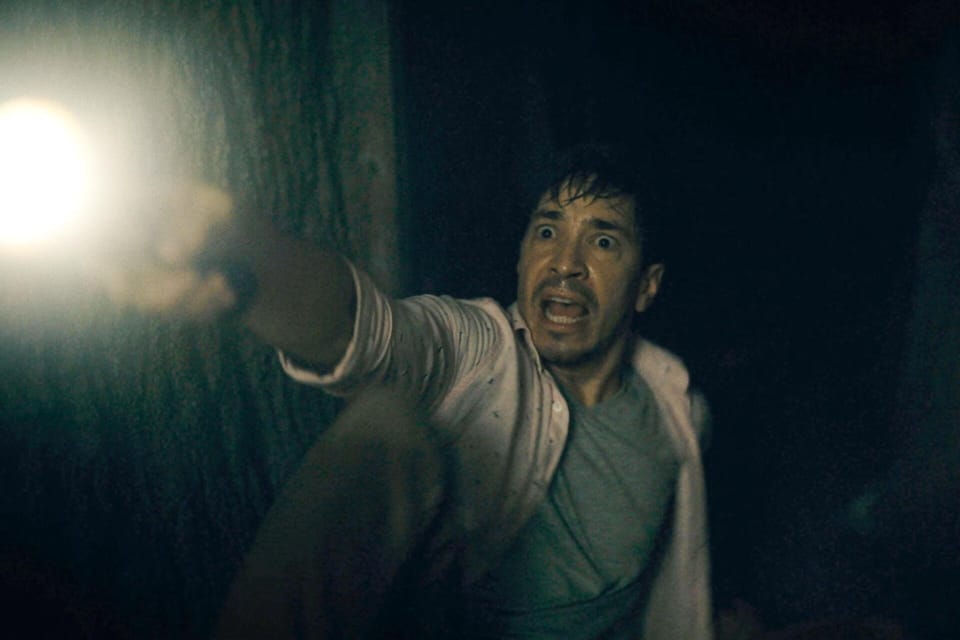

In ALIEN, the remaining crew realizes they’re in way over the head as the alien kills off two more of them. The computer will not help, and Ripley learns that the orders are that they are expendable.

In REBEL RIDGE, Terry is shot, escapes, and realizes that any legal options he had have disappeared. His new friend will have her world destroyed, too.

For all these characters, the pressure is coming from multiple fronts.

And don't be afraid of seemingly good events that undermine the primary want, like in RATATOUILLE.

Yes, Collete and Linguini kiss, and Remy reunites with his family. On their own, these are good things. Yet both are terrible for Remy’s goal to prove himself a great chef.

For an earlier screenplay of mine, I had a character in a midlife crisis.

The tensions of the story are:

- The primary dramatic question.

- His new friendship with a woman helping him.

- His relationship with his wife.

- His relationship with his son.

- The police officer on the case who wants him to let it go.

- His own sense of self.

Each one has at least a scene in Sequence 5 where the tension is turned up, and things are worse than they were before.

The increased tension leads to the end of sequence 5 where it all finally IMPLODES on him.

The goal is to kill off who the person was and for them to realize that they have transformed.

The key is to find fresh, organic, and exciting ways to do this.

Structure can put scenes in the best possible place for success, but it can't write great scenes for you. That's up to you.

Your job to surprise and delight remains.

Never forget that traditional story structure is not prescriptive.

It is a way to help guide you, not tell you what to do.

The goal of structure is narrative momentum and emotional resonance.

3 Acts, 4 Acts, or 8 Sequences -- however you write -- are shortcuts to get you to narrative momentum and emotional resonance faster.

But one of my favorite stories does not have a single bad guy in the 5th and 6th sequences. Don't force it if your story doesn't want it.

Best to look for this approach when:

- You're stuck.

- What you wrote isn't working.

- You want to embrace it from the start because why not?

But it is not required.

The Story and Plot Weekly Email is published every Tuesday morning. Don't miss another one.

When you're ready, these are ways I can help you:

WORK WITH ME 1:1

1-on-1 Coaching | Screenplay Consultation

TAKE A COURSE

Mastering Structure | Idea To Outline